Learning Objectives

This is an intermediate-level course.

After completing this course, you will be able to:

- Define and

describe transference as both a therapeutic construct and a therapeutic

process.

- Define and

describe countertransference as both a therapeutic construct and a

therapeutic process.

- Explain how archetypes trigger transference and countertransference during non-analytic therapy.

- Describe how therapists are likely to contribute to transference and countertransference phenomena.

This course is based on the most accurate

information available to the author at the time of writing. Cognitive

psychology and neuroscience findings regarding brain development, structures,

and activities continue to shed light on what were once regarded as merely

psychoanalytic concepts and processes. As a consequence, new information may

emerge that supersedes some explanations in this course.

This course may provoke disturbing

feelings in readers due to their own unresolved conflicts, but it also gives

them information about processes by which they might resolve these conflicts.

Outline

- Introduction

- Contemporary Environments and Neuroscientific Advances

- Language, Cultural Diversity, and Context

- The Phenomenon Called Transference

- Transference: Classical Definition

- Transference: Totalistic Definition

- A Description of Transference for Non-Analysts

- The Phenomenon Called Countertransference

- Countertransference: Classical Definition

- Countertransference: Totalistic Definition

- Descriptors of Countertransference

- A Definition of Countertransference for Non-Psychoanalysts

- Triggers of Transference and Countertransference

- Archetypal Material Is Embedded in Culture

- Final Thoughts

- Footnotes

- References

Introduction

Transference and countertransference are mental processes that enable us to move the past to the present and one

setting to another. We do so unconsciously. Sometimes we benefit from this

displacement, though usually only temporarily. But most of the time, sooner or later, we create problems in our lives and those with whom we interact because, in spite of their similarities, the past is not the present and one setting is not another.

We might think that these two unconscious processes will not interfere with our therapeutic efforts because we are not psychoanalysts. Transference? No. We help clients restructure the thoughts that they articulate. We help them manage feelings as they arise. We help them change behaviors. We focus on conscious processes. Countertransference? No. Before, during, and after sessions, we deal with personal issues that become apparent to us as well as to others.

Unfortunately, these presumptions are erroneous because transference and countertransference occur outside the realm of consciousness. They take place in session after session without our knowing it, whether we are trained to deal with them or not. Furthermore, they are potent, pervasive, and ubiquitous. Thus they have the potential either to make our work extremely helpful to our clients or to diminish – even prevent – the good we hope to do.

Hence the wisdom of our becoming aware of phenomena going on beneath the surface of our work, followed by our using them in such a way that they become benevolent mediators and moderators of positive therapeutic outcome. They are ever-present double-edged swords we can familiarize ourselves with by using respected psychoanalytic and psychodynamic theory and research to become proficient in transference and countertransference phenomena.

Now for a theoretical, research-based

overview.

Residing deep within the unconscious mind where there is no time (Freud, 1917), transference and countertransference become activated when similarities between the then-and-now as well as the here-and-there arise. Already encoded in subcortical neural pathways, material from our unconscious mind is propelled into our conscious mind as we try to reduce the pain of psychological phenomena we are experiencing. With the “help” of brain activity, we unconsciously revive and re-enact conflict-ridden experiences as if the past were the present and one setting were another. We transfer thoughts, feelings, and attitudes about people who resemble others. We assign them roles once played by others. We take on old roles ourselves. All unconsciously.

Why do we do this? For at least two reasons.

One is that we experienced conflicts in the past and/or in a particular setting. They were intrapersonal, interpersonal, or both. Those we could resolve, we did. Those we could not, remain. All conflicts are painful. Unresolved conflicts are doubly painful.

Because we benefit from getting get rid of pain, our brain has been evolutionarily programmed to try to resolve conflict by repeating or re-enacting it. It has unconsciously “concluded” that these methods will work, sooner or later.

In other words, we will be better off once a new experience replaces memories of a past event or another happening in another setting. For example, if our relationship with our mother was conflictual because she was abusive though she should have been loving, we assign a maternal role to our spouse and a child role to ourselves. We hope, indeed unconsciously believe, that in this re-enactment our spouse will treat us more lovingly than our biological mother did. Our conflict will be resolved and our pain replaced by well-being.

A second reason is that we live in fear – indeed terror – of some things that happened early in our life, starting in utero and with our birth. One example would be a death that we witnessed. Our little goldfish or our loving grandparents died. They shouldn’t have, but they did.

Thus we are left with a painful conflict: What we do not want to happen, happens. We do not have the power to stop it. We want the power and believe we should have it, but we don’t.

We find, however, that we can lessen our emotional pain by projecting it: transferring it from inside us to outside us. We give our parents power over death, for example, by listening carefully to them when they tell us to watch out for traffic before crossing the street lest we get killed. Then we “prove” it by obeying them. By crossing the street the way they say we should, we enjoy the illusion that death has no power over us. We get much-needed relief. That’s the good news.

The bad news is that we do not actually resolve our conflict over wanting to prevent death and being powerlessness over it. So we try again and again to gain that power through the transference process.

In other words, initially transference does solve our problem. It is a “creative projection” (Becker, 1973, 158) of something inside us to someone outside us. It serves an adaptive response to our need to empower ourselves. It allows us to survive with the help of others. We can transfer our terror of the inevitability of death – over which we are powerless – to others. As Becker (1973) explains, transference is an illusion, but a “life-enhancing illusion” (158) that brings us relief. Indeed, transference is actually necessary for our psychological well-being at the time we use it. It is the benevolent edge of a double-edged sword.

The malevolent edge? Our relief is only temporary. Others will inevitably fail to live up to our expectations that they can prevent death from happening. Death will occur, whereupon our emotional pain will be resurrected. Our well-being will give way to the pain inherent in our original conflict: wanting to prevent death, but not being able to do so.

At the same time, because we benefit from transference, we continue to use it. Even though temporary, our getting relief serves as a positive reinforcement. We have been programmed through operant conditioning to repeat the process. Again and again and again. It will become a compulsion, as noted by Freud (1912) more than a century ago.

In sum, though transference does not effectively resolve conflict, we unconsciously continue to use it. What we actually need to do, however, is learn to resolve our conflict by facing it squarely, experiencing the pain of our powerlessness, and accepting it as part of the human condition. In other words, we need to deal with transference on a conscious level. We need to undermine its influence over our unconscious mind. Indeed, we need to turn it back on itself and thus benefit from it.

In sum, we need to do what is actually possible for us: outwit the double-edged sword we call transference and its counterpart, countertransference. We need to take control over transference and countertransference, for they are the worst of masters but the best of servants (Davids, 2022).

Hence, this course:

- A course for non-analytic psychotherapists whose work is being significantly influenced by transference and countertransference although they specialize in dealing with conscious phenomena;

- A course that exposes the dangers of not undermining brain activity that imposes old schemas on new experiences simply because of similarities;

- A course that outlines how to stop displaced phenomena from running rampant during the course of psychotherapy; and

- A course that spells out how to benefit from resolving conflict, embracing the pain inherent in it, mourning what ideally should not have happened to us, and moving on.

This is the first course in a three-part

series, based on the book Transference and

Countertransference in Non-Analytic Therapy: Double-Edged Swords,

by Judith A. Schaeffer, Ph.D. (Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 2007).

(Note: To return to the course after clicking a footnote, click the Back button in your browser.)

Contemporary Environments and Neuroscientific Advances

Three developments make this course

especially pertinent for today’s mental health professionals.

First, 21st century clinicians

no longer have the option of open-ended treatment, even for dealing with

serious disorders, because of managed care’s concerns about cost-effectiveness.

They must identify and manage impediments to progress as soon as they arise so

that clients finish their work within their allotted sessions. Thus they must bring unconscious impediments to reaching their goals to the light of consciousness. In other words, treatment referred to as psychotherapy is to be a stage on which therapists help clients work “through the past and work toward the future” (Atlas, Aron, & 2018, p. 5). It is a “joint rehearsal on a stage…,” “an opportunity for” things to change “offstage” also (Atlas & Aron, 2018, p. 5).

In addition, most managed care companies require clinicians to translate outcomes into observable new behaviors and diminished, if not eradicated, symptoms. Clinicians must define what they do by functions that measure change. They must be aware of all variables that determine whether that change occurs. Thus they must know how transference and countertransference impact goal attainment.

Second, clients and their families expect

timely, ethical, and efficacious treatment. They belong to a litigious society

eager to right wrongs. Though serious errors may be rare, unaddressed

transferential and countertransferential material can result in mistakes which

clients or their families can bring to the attention of grievance boards or

lawyers. Should clients complete suicide, for example, their survivors may hold

the professionals who treated them responsible for not picking up transferential

signs of suicidal intentions.

Third, recent cognitive and neuroscientific research findings have revealed that transference and countertransference are actually instantiated in the brain (Anderson and Przybylinski, 2012; Shore, 2021; Pally, 2001; Gabbard, 2001). It is no longer scientific to deny their existence and activity in psychotherapy, no matter what a clinician’s theoretical orientation.

In other words, transference and countertransference propel conflictual unconscious material into the dynamics of both analytic and non-analytic therapy. If non-analytically oriented therapists fail to notice these displaced phenomena during their sessions, they are limited in their ability to help their clients move beyond their one-sided accounts of problematic relationships and events outside of therapy. Contrastingly, if they identify and decode that material during sessions, therapists’ perception of what is going on relationally in therapy can complement, if not correct, clients’ accounts of what happens to them outside of therapy.

As a result, clients can realize that what

is transpiring in therapy is similar to the unresolved conflicts at the core of

their presenting problems. This, in turn, can lead to conflict resolution.

Simultaneously, therapists can realize

how, through countertransference, they are also acting out old, conflictual

interpersonal issues in their relationship with clients. Then they, too, can

choose conflict resolution over mindless repetition.

In sum, "the future of psychotherapy … lies with the further development of short-term therapeutic techniques" that reduce the length of treatment while dealing "economically and effectively with the deluge of emotional and behavioral problems" that our disturbed society has spawned (Marmor, 1989, 259). Adding a focus on transference and countertransference enhances non-analytic clinicians’ otherwise efficacious work. For they are often the greatest hope for transformation in psychotherapy (Davies & Frawley,1992).

Language, Cultural Diversity, and Context

In this course, jargon is replaced by commonly used terms for the sake of readers not versed in psychoanalytic terminology. In addition, efforts are made to identify common culturally-based expectancies therapists and clients bring to their interactions. Finally, select aspects of analytic theories are placed within the context of non-analytic theories so that readers can integrate new material with what they already know.

The Phenomenon Called Transference

We all engage in transference. It is a pervasive and ubiquitous phenomenon that takes place in many situations in life (Brenner, 1982). It “occur[s] in virtually all close relationships” (Gelso & Bhatia, 2012, 384). Indeed, along with countertransference, it is “an inevitable part of relationships,” (Egan, 2022, 19). We re-experience the past in the present in a way that is inappropriate for the present (Greenson & Wexler, 1969). We misperceive or misinterpret the present in terms of the past.

We unconsciously send the “message” to select persons currently in our life that they have replaced significant others in our past. We impose what took place in one setting on what is taking place in another because in the previous one we could not resolve a conflict. We displace what still warrants our attention because it distresses us.

We will focus on the clinical setting because positive therapeutic outcomes depend on proper management of transference in non-psychoanalytic, no less than psychoanalytic, therapy (Gelso & Bhatia, 2012). Moreover, within the clinical setting, transference becomes concentrated, pronounced, and intense (Wilson & Weinstein, 1996).

Note that in this course, in keeping with psychoanalytic tradition, transference is attributed to clients and countertransference to therapists. In fact, however, both clients and therapists engage in transference and countertransference.

We’ll start with transference.

It is challenging to define transference because the term has been used inconsistently and ambiguously since Freud’s use of it at the dawn of the 20th century. Its precise meaning has never been agreed upon.

Thus, we will first focus on how transference has been described and defined in representative literature. Then we will create a theoretical definition that distills the essence of transference from its complexity. Finally, we will formulate an operational definition usable in clinical practice.

Transference: Classical Definition

Freud’s (1917) description of transference

serves as a prototypical classical definition of both a construct and a

process. As a construct, transference is clients’ displaced, early-life,

unresolved conflictual feelings and attitudes that surface in response to

experiencing their therapist. Transference is a matter of displaced memories of

affective and somatic states related to early-life significant others. It is a

matter of memories recalled by clients when they engage in therapy in such a

way that they are indistinguishable from events that occurred in the past

outside of therapy. “Transference is … the manifestation of unconscious …

memory as it intrudes upon the larger consciousness of self, breaking it up,

stunting it, and even at times, taking it over entirely” (Meares et al, 2005,

290).

As a process, transference is clients’

unconscious displacement of feelings, attitudes, sensations, and thoughts about

or toward persons in their early life to their therapist. Almost always, clients

do so because they could not resolve conflicts with those early persons. Instead,

they repressed them, burying them deep in the unconscious mind. Thus Freud

(1917) sees transference as serving the purpose of giving clients “new editions

of old conflicts” (454) so that they can resolve them. In other words,

transference is clients’ making an early-life event reappear in their

unconscious minds, an event from which they had to quickly dissociate because

of its overwhelming emotional impact (Schore, 2003a).

Lear (1993) calls transference an

unconscious movement of conflictual desire and/or belief across space and time

from one person in the past to another person in the present. It provides

another chance for clients to face psychic pain long enough and well enough to

resolve the conflict that caused the pain in the first place (Freud, 1917).

Interestingly, the unconscious mind prefers to avoid direct conflict resolution. It wants conflict to be resolved indirectly. Thus a problem: avoidance is reinforcing because it provides temporary relief from psychic pain. In time, the pain resurfaces, and transference has to be employed again. Thus conflicts never get the direct attention they need to be resolved. Another problem is that over time, this takes a significant toll on the psyche.

Pierro and colleagues’ (2008) research reveals new, useful data. The unconscious mind wants closure after gathering painful information. But particularly if it is a strong “J” on the Myers-Briggs scale, it wants closure as soon as possible. Thus people with a “J” preference (Judging) over “P” (Perceiving) are especially vulnerable to using transference as a means of avoiding conflict resolution. A reasonable deduction is that this becomes the case for “P”-preference people also because of ever-increasing distress when conflict remains unresolved (Ecker & Hulley, 1996).

At the same time, transference should be appreciated for what it does. The relief it provides at the time it is done is desirable, even necessary, for functioning, explains Becker (1973). It is an adaptive response to our awareness that we need a connection to others to cope with what life brings us. It is not possible to do so individually. In particular, we cannot stop death from happening, but we can cope with its inevitability by transferring our terror of death and our need to have power over it to another person. In other words, transference does solve a problem. It is a “creative projection” (Becker, 1973, 158). It is an illusion, but a “life-enhancing illusion” (158).

Transference as Involving Projection and Introjection

In the therapeutic setting, transference is

the projection of some aspects of a figure in the client’s past onto the

therapist. For example, as clients displace their fear of their critical mother

to their therapist, they attribute to their therapist their mother’s habit of

criticizing them. “You are like my mother,” the client senses, “and like my

mother, you will criticize what I do. I am no more powerful to stop you

than I could stop her. But I can at least placate you by doing the homework you

assign.” Another example would be Caucasian clients unconsciously projecting their own undesirable and unacceptable qualities on racial-minority therapists and making Whiteness a standard against which therapists are evaluated (Tummala-Narra, 2019).

As clients engage in projection, therapists engage in introjection. They unconsciously receive what clients send. “You perceive me as your critical mother and believe I will criticize you,” therapists sense. Then they tell themselves, “I can do nothing to prevent you from fearing my criticism, but I can come to your assistance by overlooking that you did not do the homework.” Or racial minority therapists whose countertransference mirrors their clients’ transference unconsciously tell themselves, “I must be exceedingly careful to come across as having the mannerisms of White people.” Ironically, noticing this subtle effort, clients then tend to confirm their belief that their therapists are indeed not White. They might even unconsciously conclude that their own inferior work, as non-White persons, is the reason they are not making progress.

It is of utmost importance to note that therapists engaging in introjection receive projections without identifying with them or owning them and the feelings connected with them (Stamm, 1995). They “accept” projections without necessarily confirming the perceptions inherent in them (Schafer, 1968).

Rather, therapists’ confirmation of a projection depends primarily on their own countertransference: displacement of their own unresolved conflicts (Westen & Gabbard, 2002). It depends on “the extent to which the [client’s] projection meshes with aspects of the therapists’ unresolved … conflicts ….” (Meissner, 1996, 43). Some therapists, for example, have not resolved their own conflict over mothers being critical of their children although they should accept them unconditionally. It is likely that their own mothers were routinely critical and, as a consequence, they hold templates of mothers as critical. Thus they unintentionally confirm their clients’ projection of them as critical. Consequently, they engage in some form of fault-finding. They routinely bring their clients’ attention to being slightly late, for example.

On the other hand, therapists who have resolved their own conflict over mothers being critical are not likely to confirm a projection of them as critical. They do not find fault with clients who send them projections of their being critical. They do not ordinarily call clients’ attention to being slightly late. Or they ask to explore with them client why they did not do their homework. They come across to their clients as respectful and/or curious rather than critical. 1

It is also important to keep in mind that clients who project do not recognize what they project as their own. It feels foreign to them. Something that they dislike seems to be coming at them, but it is not

theirs. They can sit back and criticize their therapist for what appears to be his or her negative trait or habit, oblivious to the fact that they are finding fault with themselves and thus projecting that unwanted trait. Hence, though the authors of the DSM-5-TR do not address transference directly, they do classify projection as a defense mechanism that is “almost invariably maladaptive” (Kupfer et al, 2013, 819; American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Transference as Unconscious

Freud (1912) insisted that transference be regarded as fundamentally unconscious. Though clients may become aware of something calling forth their transference, they are not conscious of the relationship between that present stimulus and a past phenomenon. Their feelings about their therapist, for example, seem reality-based in the here-and-now.

Thus transference has been described as unconscious “meta-language” that carries meaning from clients to therapists.

As neuroscientist Schore (2003a) explains, the right hemisphere of clients communicates emotional states in nonverbal ways to the right hemisphere of therapists. Operating on a symbolic dimension (Lacan (1966), it uses symbols to convey information to the conscious mind (Epstein, 2023). 2

Thus, for instance, therapists receive the message on some instinctual, subliminal level that they have become their clients’ mother figure, for example, and that their clients feel toward them the same way they felt toward their actual mother. Therapists might later recall a gesture or posture of clients that probably served as a stimulus for their awareness, but at the time they were not conscious of that stimulus. Their clients simply and mysteriously sent a message which they simply and mysteriously received.

As an unconscious process, transference is no more accessible to clients’ conscious mind than other unconscious processes. While they may become distressed by bodily sensations, fantasies, dreams, and other manifestations of transference, they do not connect their distress with transferred material. As a result, they either move on to an issue of which they are conscious, or attribute their distress to a non-displaced, purely here-and-now phenomenon. Clients who transfer to therapists their fear of a critical mother, for example, might experience cold, metallic sensations. They might unwittingly assume postures indicative of avoidance as they project a negative maternal role onto their therapist. But, if they try to find an explanation for what they feel or do, they simply attribute what is going on to their therapist’s negative ways.

Without learning new skills, they are not able to access the material they have displaced. However, with these skills, they can process displaced material and thus prevent a maladaptive behavioral response to a transferential experience. Transference itself, along with an unconscious reaction to it, cannot be prevented, Anderson and Przybylinski (2012) emphasize. But after picking up cues or manifestations of transference, clients can choose adaptive behavioral responses to transferred material. To use Anderson and Przybylinski’s (2012) excellent recommendation, therapists can help clients design and install an if-then schema that they can then quickly engage. “If this happens, then I will say/do this” can guide their behavior, be it verbal or non-verbal. Thus in time, they will form the habit of responding differently after their initial reaction.

Transference as Fantasizing

Without such an intervention, most clients will rarely subject transferential material to reality testing. They will not use their conscious mind to distinguish facts from fantasy. If their conscious mind does anything, it will disregard the displaced material as an illusion unworthy of further attention.

Thus transference is a form of unconscious fantasizing that requires the reality-testing left hemisphere, or left brain, to be held in abeyance (Herron & Rouslin, 1982). Transference occurs naturally because the right-brain-to-right-brain communication at the heart of transference by and large prevents the left brain from acting.

Consequently, the transference process involves erroneous perception and extremely simplified cognition that work together to distort reality. Furthermore, this activity of the right brain occurs immediately and effortlessly upon cues of similarity being detected (Anderson & Przybylinski, 2012). One or two similarities are recognized, while many dissimilarities are dismissed. Clients simply fantasize, for example, that their therapist is another critical person with whom they have had a conflictual relationship. They do not take time to evaluate whether that fantasy matches reality or is a figment of their imagination.3 Indeed, it usually does not even occur to them to do so for up to two weeks (Glassman & Anderson, 1999).

In sum, according to its classical definition, transference is merely a repetition of wishes, feelings, fantasies, attitudes, and bodily sensations initially experienced in relation to early-childhood figures and now inappropriately and unconsciously displaced to the therapeutic setting. The client’s transferential experience is something like this: “I want an accepting, non-critical mother, and I do not perceive you as one, therapist. I perceive you as no different from my actual mother. Consequently, I feel the same negative feelings toward you that I felt toward her.”

According to the classical definition of transference, the fantasy that begins and sustains transference can be accounted for by similarities between the therapist and an early-life significant other. The client’s here-and-now experience of the therapist and the client’s there-and-then experience of another become temporarily identical (Nunberg, 1951). The past is reconstructed in the present as the client regresses to an early-life stage, notices similarities between the therapist and the early-life figure, and allows those similarities to guide perception. The therapist is perceived as so similar to a person in the past that he or she is the same person. Thus the therapist becomes a person with whom the client is still conflicted (Freud, 1940).

In other words, the past predetermines the present in that clients cannot help but perceive their revived ideas, feelings, and sensations as simply present realities (Chodorow, 1996). Transference just happens when something in clients’ experience of their therapist, usually of a sensory nature, serves as a reminder of a similar experience recorded in the clients’ memory. Even slight resemblances such as body scents, facial hues and features, gestures, tone of voice, or similarity in names become “kernels of truth” (DeLaCour, 1985) that allow clients to re-experience the entire pattern of their relationship with another person who is still significant on an unconscious level. They even sense the setting and atmosphere in which an encounter with the original person occurred (Rioch, 1943).

For example, “My critical mother had piercing eyes,” the client recalls on an unconscious level, “and so does my therapist. My therapist seems to be my critical mother. She is her.” The stage has been set (Anderson and Przybylinski, 2012). The play can – and does – go on.

Thus “transference is its own motivation;” [it is] “a built-in pattern that impels [clients] to engage in a particular type of similarity-judging, memory-priming pattern of behavior” (Levin, 1997, 1141). It is driven by a compulsion that Freud (1912) termed a repetition compulsion.

Transference as Positive and/or Negative

Originally, Freud (1912) regarded transference as either positive or negative. Either its inherent conflict is overshadowed by pleasant or enjoyable feelings, or it is inundated by disturbing or painful feelings. In the case of positive transference, Freud (1912) believed that clients transfer the needs that a past figure did not meet to their therapist, hoping that the therapist will meet them. A healthy part of the client hopes to create an outcome different from experience. That part wants the present to be better than the past. So more often than not, clients idealize their therapist (Churchill & Ridenour, 2019). In the case of negative transference, in projecting their negative feelings toward a past figure onto their therapist, clients sustain their fear that their therapist will behave like the past figure. An unhealthy part of the client has a desire to repeat what is known, even if it is harmful, because it is familiar and safe (Stark, 1994). The client is invested in keeping things as they were. Indeed, clinical evidence supports the conclusion that “when negative transference predominates, the therapeutic relationship and its effectiveness will be diminished if the therapist does not aid the [client] in gaining an understanding of the sources of the negative experience and perceptions. In the absence of insight, [clients] will simply accept the accuracy and credibility of their negative projections on the therapist …. [They will] … simply believe that the therapist thinks or feels negatively toward [them] or that [their] negative reactions to [their therapist are] warranted” (Gelso & Bhatia, 2012, 388).

Freud (1912) advised therapists to simply ignore positive transference. Or they could regard it as an asset because it had the potential to help form the therapeutic alliance. In contrast, therapists were to interpret negative transference because it was a liability that, left alone, would weaken or destroy the therapeutic alliance.

In time, however, clinicians found that positive transference was very potent. It proved even stronger and more enduring than negative transference (Berk & Anderson, 2000). It also proved to be more subtle and therefore difficult to detect (Anderson & Przybylinski, 2012) and thus detrimental. For instance, it could encourage a culturally re-enforced “gentleman’s agreement” (Wolstein, 1996, 507) to keep the therapeutic relationship non-confrontational and thereby avoid difficult conflict-resolution work.

Hence, even some early Freudian theorists advocated interpreting positive transference if it seemed to interfere with therapeutic work. Equally important, they began to note that negative transference could become a positive experience if therapists were able to make their clients aware of their transference and embark upon the hard work of conflict resolution. 4

Transference as Conflictual

Though a paradigm shift within

psychoanalysis has de-emphasized conflict in transferred material (Anderson

& Przybylinski, 2012; Olds, 1994), the concept of conflict remains central

to the original classical definition of transference. Transferential conflict is

an incompatibility of conflicting desires “such that satisfaction of one such

motive has a negative influence on another” (Westen, 1988, 172). Satisfaction

of a sexual wish, for instance, can conflict with one’s moral values.

Transferential conflict can also arise

from a significant difference between what one needs or wishes and what one

gets. A child who needs protection from a parent, for example, and is instead

neglected, will experience conflict. The child will find it difficult to

reconcile his need to be protected with the neglect he experiences, thinking,

“Should I not need protection?" Or “Shouldn’t I get the protection that I

need?”

Conflict is to be expected even from a

neuroscientific perspective because wishes, beliefs, values, and goals are likely

to be processed by relatively independent neural circuits. In addition, each

hemisphere of the brain forms two independent self-representations or

self-images, one stored in the left and one in the right, that are used again

and again in new situations. Clients can wish for something that their right

brain likes even as their left brain tells them it is illogical to have that

wish. Similarly, clients can choose to endure what they experience as harmful

even though it is painful. For example, to keep some kind of relationship with

a parent, which would be in line with their right brain image of who they are

in a family, clients can allow themselves to continue to endure neglect at the

hands of that parent, which would be a violation of their left brain image of

themselves as rational and therefore not wanting to endure painful neglect.

Clients

who are engaged in transference attempt to dissipate its inherent conflict by

repressing their memory of it or blocking it out of consciousness. They hope to

stop realizing that they have desired a relationship with a neglectful parent,

for example, or have been neglected because they kept a relationship with the

parent. This, of course, lays the groundwork for the phenomenon of transference

to occur when new, similar circumstances remind clients of their old desires or

experiences of not having their needs met. When their therapist has to cancel

their appointment because of an avoidable emergency, for example, clients will

recall the times they were neglected, and thus will feel overwhelmingly

neglected by their therapist.

Transference: Totalistic Definition

The totalistic definition of transference, which is broader than its classical counterpart, was actually formulated early on as Freud’s contemporaries disagreed about whether transference should be restricted to displacement of phenomena from the early past. Jung (1905/1906), for example, saw transference as clients’ unconscious displacement of their relationships with others from any time in their lives.

Others asked if transference could not also be based on clients’ experiences occurring outside the therapeutic setting? Could it not be interpersonal in addition to intrapsychic in that the therapist participated in, contributed to, or even instigated its formation? Indeed, if transference were to be a useful construct during actual therapy, should it not include these experiences and interactions?

Indeed, as early Freudians focused on parental figure links to patterns revealed in the transference, they found it even more important to focus on clients’ reactions to their therapists – as representing others in their present life – than to help clients discover the early-life origins of their problems.

Early Freudians also noticed that emphasizing the early-life sources of transferential patterns could strip clients of defenses they still needed for functioning (Bauer & Mills, 1989). They might not be able to face the fact that the parent who was more protective of them than the other parent failed to do so on a very significant occasion. They might need to defend themselves against that painful realization by engaging in reaction formation, a defense that has allowed them to keep, even embellish, positive aspects of their parent’s image. However, as adults, they had the resources to deal with how someone in the present, namely their therapist, was disappointing them.

Early Freudians also noticed that conflictual material was at least implied in issues that brought clients into therapy. Moreover, tensions and conflicts that occurred during therapy were strikingly similar to those occurring outside of it, making therapy a virtual “slice of life.” It was a slice of a particular client’s life abetted by a particular therapist.

Hence, by the mid-1920s, Rank and Ferenczi (1925) theorized that focusing on displaced material that was impacting the therapist-client relationship – a here-and-now phenomenon – would eventually expose earlier conflicts still needing to be resolved. They seriously questioned whether positive therapeutic outcomes depended solely or even primarily on resolving the early childhood conflicts revealed in transference.

5

Thus for most theorists and therapists, including Freud, the concept of transference eventually acquired a more inclusive meaning that is now its totalistic definition. Transference was the client’s unconscious displacement of attitudes, feelings, sensations, and thoughts from another person in the client’s life – past or present, within the therapeutic setting or outside it – to the therapist in an attempt to re-enact and resolve conflict.

The totalistic definition of transference becomes clearer when contrasted with the classical definition, point by point. Note that the elements they share are not re-examined.

Transference: A Re-Enactment

In the totalistic tradition, transference is a re-enactment rather than a repetition. Motivated by a powerful desire for positive outcome, clients unconsciously assign roles and functions previously taken by others to their therapist in the hope that their needs will finally be met. Clients who unconsciously desire “role-relationship” with another demand “role-responsiveness” of their therapist (Sandler, 1976, 44). They insist that their therapist be an active participant. They prod, provoke, and coerce. As a result of this manipulation, their therapist unconsciously participates. Thus the client “actualize[s] an internal scenario within the therapeutic relationship that results in [the therapist] being drawn into playing a role scripted by [the client’s] internal world” (Westen & Gabbard, 2002, 101) in their unconscious effort to resolve conflict.

Especially tell-tale of this interpersonal dynamic are powerful emotional reactions in therapists that make them step out of their customary roles. So is their clients becoming self-destructive, noticeably foolish, or acting in wild, exaggerated ways (Weiss, 1993).

Clients also set up re-enactments in an unconscious effort to disprove long-held, pathological beliefs, particularly those about their self-identity and self-esteem (Gazzillo et al, 2019). Clients “are highly motivated, both consciously and unconsciously, to disconfirm [their pathogenic beliefs] and get better” (174). Moreover, they have a more or less articulated, albeit unconscious, plan for doing so (Gazzillo et al, 2019; Weiss, 1998). For example, they want their therapist to respond to them in such a way that they can believe they are valuable and competent. Thus they use transference to test reality, saying to themselves “If I am helpless, then my therapist will take over and solve my problems. If not, she will return them to me so that

I take responsibility for doing so.” As Cooper (1987, 518) puts it so well, transference is an “adventure from which [clients hope to] emerge changed and renewed.”

6

The totalistic transference emphasizes the therapist’s unconscious participation through a phenomenon called countertransference. It is an integral part of a transference phenomenon. Transference provokes countertransference (Racker, 1968). Similarly, countertransference provokes transference.

Thus transferential-countertransferential re-enactment underscores an early observation of Freud himself: “It is a fundamental demand of all transference, underlying all the particular demands, that [the therapist] … should participate in a world endowed with particular meaning” (Freud, 1900, 747). As the client unconsciously attempts to re-animate problematic interpersonal relationships, the therapist unconsciously cooperates. Client and therapist become enmeshed in a complex interaction, “a kind of psychic force field compounded out of intermingled transference and countertransference processes” (Meissner, 1996, 42). The transferential-countertransferential “dialogue” between client and therapist serves as a bridge between them, observed Ferenczi (Fleischer, 2023).

Transference: A Dynamic Phenomenon

According to its totalistic definition, transference is dynamic rather than static. It evolves as clients derive positive or negative meaning from their therapists’ seemingly benevolent or malevolent words and actions. Noticing such indicators of attitude as voice quality, degree of energy, level of professionalism, and person-to-person warmth, clients quickly project their feelings and attitudes toward pre- or non-therapeutic persons onto their therapist. Moreover, they see to it that their projections become forceful and intense when they encounter a particular therapist who has traits they associate with their relational conflicts.

Seen in a slightly different light, totalistic transference is dynamic in that it is an organizing activity in which clients unconsciously engage in response to a number of variables: early-life and later-life memories of others, current experiences with others, and the attitudes, words, and actual behaviors of therapists in the present (Stolorow, 1993). Clients impose the organization of prior perception upon the present. They actively, though unconsciously, shape here-and-now psychic reality.

6 They structure and

organize present experience in such a way that the past can come alive and be

re-enacted (Bachant & Adler, 1997). They want the psychic pain they still

hold to disappear.

In other words, totalistic transference is

not simply a matter of clients unconsciously reviving old pictures, thoughts,

emotions, and sensations and perceiving them as present reality. It is not

just, “You seem to be my parent.” Rather, it is “You are my parent. I

know so. I say so. Furthermore, you will love me as a parent and take away my

pain.” Said simply, in the totalistic tradition, transference is an unconscious

insistence that memories of others’ past negative behaviors get replaced by positive

experiences with present-day others. 7

Indeed, totalistic transference is dynamic

in that it is a two-fold process in which therapists unwittingly engage. First,

they act in such a way that they offer clients an opportunity to re-enact past

or non-therapeutic relationships. Their characteristics, interpersonal

behavioral patterns, and traits make transferential role-playing possible. They

actually inspire the very roles their clients project. They collaborate with

clients in writing scripts for the roles they will be asked to play.

Second, as their own transference – referred

to as countertransference – is triggered, therapists with a corresponding

unresolved conflict unconsciously transform the roles their clients assign them

in subtle, idiosyncratic ways. They shape a transference enactment by

responding subjectively to the projections they receive. They give their clients

“additional material” with which they can continue to enact transference.

Therapists who indicate that they even slightly disagree with something their

clients say, for example, permit their clients to embellish their projection of

their critical mother. 8

Recall that the classical definition

already implies that therapists provide “kernels of truth” (DeLaCour, 1985) for

clients. While consciously performing their roles, therapists also

unconsciously contribute other, fragmentary, disguised variables that serve as

reminders of persons in clients’ conflictual past. 9 Therapists momentarily use a harsh voice, for instance, and thus give clients

the cue they needed to notice similarities between therapists and

persons outside therapy who verbally abused them.

However,

the newer totalistic definition goes on to add that clients unconsciously send

a message to therapists that they have already activated their potential to

take the role now being assigned them. 10 Those who could be critical, for example, are already being perceived as critical.

Therapists then unconsciously introject the message and, if their

countertransference permits it, enact the role of a critical person. They might

use a slightly disparaging tone of voice, for instance, or use it to a greater

degree than usual. 11 Thus the totalistic definition of transference emphasizes the powerful

influence that therapists’ personal, countertransference-based characteristics

and behavior have on the content and shape of clients’ transference (Cooper,

1987).

Transference: A Displacement of

Interpersonal Experience

Totalistic transference is displacement of

any interpersonal experience in life, not just early-life experience. It adds

the recent past to the early past as well as the present to the past as sources

of clients’ conflicts (Strachey, 1934, 1969). The totalistic definition of

transference adds what is going on interpersonally outside of sessions to what

is transpiring in sessions and adds what has been going on

intrapsychically in the client since infancy. An example would be the

increasingly common negative perception of immigrants in the U.S. As

Tummala-Narra (2019) points out, “Perceptions of [immigrants] … based on

projections of unwanted parts of the self … are becoming justifications for the

demonization of racial minorities.” (4) 12

With Jungian theorists, the totalistic

definition of transference has become so broad that it includes archetypal

phenomena: universal and transpersonal material common to humanity throughout

the ages and therefore able to serve as prototypic interpersonal templates.

Universal archetypes trigger transference, and transpersonal archetypal themes

form its content. Age-old, worldwide, collective, and transcultural material

emerges as the client’s own (Jung, 1966). The archetypes reveal their powerful

relevance in generation after generation, culture after culture, and individual

after individual (Dieckmann, 1976).

Thus, according to Jungians, transference

is both a new experience and an enactment of an old one, be it unique to the

individual or inherited. It is a here-and-now personal phenomenon based on a

then-and-there universal memory. “I am an older sibling in competition with my

therapist, my younger sibling,” a client fantasizes, for instance, in response

to a trigger related to scarcity and universalized in the Sibling Rivalry

Archetype.

A Description of Transference for Non-Analysts

The following description of transference

will serve as its definition in the rest of this course. It is an

operationalized definition that provides a concrete template by means of which

non-analysts can verify suspected transference phenomena.

Transference is matter of the following:

- Clients

unconsciously and compulsively attempt to re-enact in therapy unresolved

interpersonal conflicts originating in the past or outside of therapy, along

with conflicts they hold because of archetypal phenomena.

- Clients

unconsciously attend to similarities between their therapists and others with

whom they have unresolved conflicts during their therapy sessions. They then

let these similarities motivate them to displace past phenomena to the present

therapeutic setting. They project qualities of other persons onto their

therapists.

- Clients

unconsciously organize their relationship with their therapist during sessions

in such a way that, without consciously addressing past or present conflicts,

they can reduce or eliminate their emotional pain.

- Clients

assign to their therapists roles originally played by significant others with

whom clients are still conflicted. They attempt to re-enact conflictual

experiences and have them “turn out well.”

- Concurrently, therapists introject or unconsciously take in their clients’ projections:

messages that they are like others and behave as they did.

- Concurrently, clients unconsciously permit their therapist to project to them pre- and

extra-therapeutic material that they can develop into transference phenomena.

- Both clients and therapists unconsciously permit themselves to be influenced by

universal archetypes that suggest they play certain roles and assign

corresponding roles to each other.

The Phenomenon Called Countertransference

Countertransference: Classical Definition

Classical countertransference is a mirror of classical transference. It is therapists’ own transference being elicited by clients’ transference (Freud, 1910). It is therapists’ feelings and attitudes toward a significant early-life figure being displaced to the client (Freud, 1912).

When defined as a construct, countertransference refers to therapists’ unconscious reactions to clients’ feelings and attitudes toward a significant past figure being displaced by therapists themselves. It is an automatic reaction quickly triggered by therapists’ own unresolved conflicts.

In other words, countertransference is a matter of therapists’ repressed, early-life, unresolved conflictual feelings and attitudes that surface as they experience clients’ displaced conflicts. Countertransference is a fusion of past and present. When old material is transferred to the therapeutic setting, the past becomes the present.

When defined as a process, classical countertransference refers to clients’ transferential communication “calling forth” from their therapists’ unconscious mind feelings and attitudes related to their own early-life conflictual experiences. Although there can be some exceptions, ordinarily this “calling forth” depends on two dynamics.

One is that clients unconsciously send memories of early-life conflictual experiences to their therapist’s unconscious mind, and the therapist unconsciously receives them. Neuroscientist Olnick (1969) explains that therapists’ right-brain communication receptors are tuned in to their clients’ right-brain communication expressions. Using subliminal sensory signals, clients project onto their receptive therapists the traits or habits of persons that led to the clients’ early-life conflicts.

The second dynamic on which “calling forth” depends is that therapists already have unconscious memories of their own early-life conflictual experiences that can be “called forth” by clients’ transference. They have conflict-based templates that permit them to transfer presuppositions or presumptions to the therapeutic setting (Herron & Rouslin, 1982). “You are a sibling who has bullied me and are about to do so now,” a therapist unconsciously thinks about a client who has projected onto him the traits of a sibling who once victimized him. Thus countertransference “is determined by the fit between what [the client] projects onto the therapist and what preexisting structures are present in the therapist’s intrapsychic world” (Gabbard, 2001, 9).

In the classical tradition, countertransference refers

only to those reactions caused by displaced psychic conflicts that clients have transferred from an early-life relationship to the therapeutic relationship and that therapists still have with persons from

their early years. These conflicts are triggered by right-hemispheric, non-verbal communications of clients and therapists, but they are not based

primarily on what occurred during therapy sessions. Consequently, they are not justifiable in terms of objective data. They are inappropriate or irrational. Therapists may be annoyed by clients who come late for a session, for example. But if countertransference is not at work, therapists are not outraged. On the other hand, if therapists were frequently kept waiting because of the insensitivity of a parent and they are transferring that attribute to their clients, they become outraged.

13

Countertransference,

like transference, is subject to a habit of the unconscious mind called repetition

compulsion. Because of repeated projection and introjection, feelings and

attitudes in the therapist’s unconscious mind are easily and quickly re-activated.

They are not subjected to reality testing but simply make therapists

unconsciously re-use old perceptions and re-make old judgments. They set the stage on which therapy plays out.

It is generally presumed that therapists

introject or unwittingly take in clients’ projections before clients introject

therapists’ projections. However, it is more likely that introjection, like

projection, is a simultaneous activity of therapists and clients. Or, clients

may introject first as therapists provide “kernels of truth” on which clients

can base their transference. These “kernels” may

be not only the therapist’s piercing eyes – which are like the client’s mother’s

eyes – but also the therapist’s subtle habit of criticizing others that

corresponds to her client’s schema of mothers as persons who invariably find

something wrong with their child. Indeed, in the classical definition,

countertransference is a matter of clients’ transference activating therapists’

unconscious templates of what life and people are like because of therapists’

own early-life unmet needs and unfulfilled wishes.

Countertransference occurs automatically.

Then, as soon as it is suspected by the conscious mind, it is itself repressed

or dismissed. Signs of its presence, called derivatives or manifestations, may be noted by the conscious mind – the therapist may become aware of shuddering

in disgust, for example – but countertransference as such takes place within the

inaccessible realm of the unconscious mind. That part of the psyche, which is

simply called the unconscious, is a “receptive organ” (Freud, 1912, 115) or

“delicate receiving apparatus” (Money-Kryle, 1956, 341) that has no choice but

to introject what another person projects. It is unable to use the conscious mind’s

reality-testing function to distinguish between fantasies of its own making and

objective reality. It fuses past and present. It incorporates one person within

another. It distorts perception, impairs insight, and clouds judgment.

Hence a therapy scenario such as this. The conscious mind knows “I am not this client’s younger sibling,” even as the more influential unconscious mind concludes, “Because I feel like my client’s younger sibling, I am him.”

In sum, classical countertransference occurs because of therapists’ conflictual wishes and needs. Therapists who have not resolved their conflict between their wish for their mother’s unconditional love and her real-life withholding of love, for example, tend to experience older, maternal clients as limited in their //ability to cherish others, including their therapist. This, in turn, informs the therapists’ attitude and behavior toward these clients. They feel distanced from their clients. They withdraw from them. They minimize their verbal interactions with them. Thus unless countertransference is detected and processed by the therapist's conscious mind, it is very likely to undermine positive therapeutic outcome. If detected and worked with, however, countertransference can lead to a positive therapeutic outcome. Like transference, it is a double-edged sword.

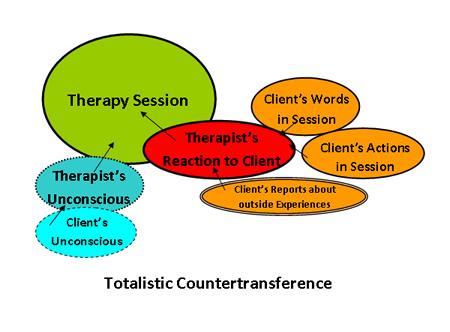

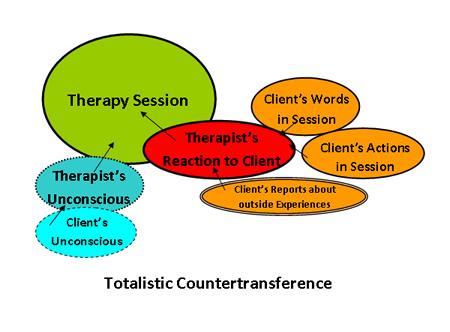

Countertransference: Totalistic Definition

Countertransference becomes even more

complex in its totalistic definition. Because of widespread disagreement on how

totalistic countertransference is defined, we will explore just two

representative definitions.

At the start, it is important to note that

these two definitions, like most totalistic definitions,

presume the following three elements of the classical definition. First,

therapists’ countertransference takes the form of emotions, sensations, and

cognitions related to their clients. Second, countertransference involves

unresolved conflict that has been repressed in the unconscious mind of therapists.

Third, besides being dependent on projection and introjection,

countertransference is also dependent on identification, a phenomenon

wherein clients and therapist actually see parts or aspects of the other person

as belonging to themselves. They identify it as their own.

The Broadest Definition

According to Heimann (1950), totalistic

countertransference refers to all attitudes and feelings that therapists

experience toward clients, unconscious as well as conscious. It is the total

reaction of therapists to their clients in the therapeutic setting. It

consists of therapists’ unconscious, unresolved conflicts that are elicited by

clients’ transference, as well as therapists’ conscious, justifiable reactions

to actual experiences during therapy. It includes reactions to what clients say

and do in therapy and to what they report they are going through outside of

therapy (Kernberg, 1987).

Thus the broadest definition does not limit countertransference to unconscious, early-life material, to the past, to the subjective, or to fantasy. Rather, it is therapists’ response both to real attributes of clients and to attributes that therapists merely fantasize. A client might indeed be boorish, but a therapist might label him as boorish simply because he resembles a boorish person in the therapist’s past. Likewise, especially with Jung (1905/1906), countertransference is a reaction to present and recent material no less than early-life material. For example, if therapists are being glorified by interns whom they supervise, they might unconsciously assign similar adulatory roles to their clients. Then, when clients do not admire them, they are disappointed.

In other words, totalistic countertransference, which is subjective in that it arises within the mind of the therapist, may also have an objective component in so far as it is a reaction to clients’ actual behavior in sessions. It is a product of the present therapeutic relationship as well as the past and present non-therapeutic relationships that both clients and therapists transfer to their therapeutic encounter.

Interesting new research supports the theory that totalistic countertransference is neither rare nor infrequent. Gazzillo and colleagues (2015), for example, have found that the emotional reaction of all 144 clinicians studied to clients with personality disorders was helplessness, with the degree of helplessness dependent on the level of the client’s overall pathology. Furthermore, clinicians’ reaction to clients with a histrionic personality disorder was a feeling of being overwhelmed and sexualized. Their reaction to clients with narcissistic personality disorders was a desire to be parental even as they felt humiliated. Their reaction to clients with phobic personality disorders was simply a desire to be parental.

In its broadest sense, totalistic

countertransference consists of affect, cognition, and bodily sensations

stemming from unmet needs of both therapists and clients. It is

occasioned by what clients do to therapists both knowingly and

unknowingly. It is sparked both by what therapists bring to sessions

independently – what is “set to go” – because of therapists’ previously fashioned

conscious and unconscious schemas regarding people and by the professional

roles that therapists believe they must play. They may transfer a maternal role

to the therapeutic session, for example, when working with a distraught client

who strikes them as child-like.

Totalistic countertransference is a matter

of therapists’ experiencing toward clients the feelings and attitudes that

therapists originally associated with other persons with whom they still have

problematic interactions (Racker, 1968). It is also a matter of therapists’

unconsciously assigning to clients roles peculiar to their own interpersonal

experiences and the ways they define themselves in the present. Therapists send

messages “asking” their clients to take certain roles that will meet their

still-unmet needs and fulfill their still-unfulfilled wishes.

For example, therapists who have suffered

from dominating fathers tend to assign a dominating role to their clients,

usually older males, in the hope that their clients will choose not to

dominate. Thus they will meet the therapists’ long-held need for

self-determination. Similarly, therapists who see their role as quasi-medical

tend to assign patient roles to their clients. They give them a chance to be

healed and thereby fulfill their desire to heal others.

Of course, therapists’ countertransference

also creates opportunities for clients’ transference. In behaving in certain

ways on their own, therapists create opportunities for clients to relate to

them in ways reminiscent of clients’ relationships: early, later, and

contemporary. As recipients of therapists’ behavioral tactics, clients

experience their own unresolved conflicts and re-discover aspects of their

conflicted selves. Therapists who are somewhat authoritarian, for example,

enable clients to return to a student role if that role has remained

conflictual for them. In the countertransference, clients find themselves,

Sandler (1976) says succinctly.

In addition, in its broadest sense,

totalistic countertransference includes transpersonal and transcultural

archetypes that emerge as therapists’ own material and get transferred to the

therapeutic setting. In fact, according to Jung (1966), archetypes are the

major triggers of both transference and countertransference. Therapists might

regard themselves as superior to their clients, for example, because of the God

and Goddess Archetype. They might classify clients as inferior to them even as

therapy begins or do so at the time clients transfer their tendency to become a

victim from an early-life situation to the therapeutic setting.

Racker (1968) believed that totalistic

countertransference depends not only on projection and introjection but on identification: a phenomenon whereby clients and therapists actually see parts or aspects

of the other person as belonging to themselves. Identification includes (1)

projective identification, a mental activity engaged in by one person; and (2)

introjective identification, a corresponding mental activity engaged in by

another person. In analytic tradition, projective identification is attributed

to the client and introjective identification, to the therapist.

Klein (1946) first defined projective identification as children’s fantasies of ridding themselves of unwanted feelings by assigning them to someone else. Today, however, most theorists define projective identification as the omnipotent fantasy that we can split off an undesirable part of our personality, put it and emotions that it incites into another person, and then recover a modified version of what was put into the other person (Grinberg, 1962; Ogden, 1982). Because we unconsciously pressure others to identify with or own what they receive, and that they ordinarily succumb to that pressure, we experience a feeling of oneness with those persons (Schafer, 1977).

Schore (2003a) adds that those engaging in projective identification become dependent on the persons into whom they project the unwanted part. They need the persons to learn how to deal with the part. They might even need to collaborate with the recipients to manage it. For instance, clients who have anger management problems first unconsciously put their anger into their therapist. They then unconsciously observe what their therapist does with the anger. They note how the therapist momentarily stops talking, for example, so that she will be calm when she says something. Interestingly, clients will unconsciously talk in a very calm way to help their therapist regain composure.

In the course of projective identification, clients unconsciously put into their therapist a part of their identity that they are unable or unwilling to own as theirs. Concurrently, the therapist participates by unconsciously internalizing that part in a process called introjective identification.

Clients use projective identification to put into their therapist a distressful part of themselves for one of two reasons (Hinshelwood, 1999). The first is that the distressful part is related to memories of an experience in which others treated them badly, which implied that they were bad persons. The second is that the distressful part is the cause of the clients' treating someone else badly, which also implies that they are bad persons and makes them not want to own what they are doing and the guilt it carries. It is either, “You are abusing me and therefore distressing me. I must be a bad person;” or “I am treating you badly and cannot stand that in myself. I cannot stand being a bad person.”

When they become recipients of what their clients’ project, therapists identify with their clients and/or with those who have been affected by them. Grayer and Sax (1986) note that in any given session, therapists usually move back and forth; identifying first with the client, then with a person affected by the client, then with the client, and so forth.

Projective identification is a three-step process that occurs quickly. First, clients unconsciously put into their therapist an undesirable part of themselves to defend themselves against psychic pain (Ogden, 1982). They unconsciously scapegoat: place into their therapist something in them that feels so unbearable that it must be expelled (Heath, 1991). Indeed, they do this so completely and so unwittingly that they attribute what they expel no longer to themselves but to their therapist. Abusive clients who are unable to tolerate that trait in themselves, for example, engage in projective identification by perceiving their therapist as abusive. In that way, they experience their therapist, not themselves, as abusive.

Second, clients exert pressure on their therapists to experience themselves and behave in a way congruent with the projective fantasy they have received (Ogden, 1994). Clients stimulate in their therapists intense, unexplained, and ego-dystonic emotions (Maroda, 1995) which cause them to undergo an affective experience in line with what they receive. They feel abusive, for example, and detest it (Kernberg, 1987). Moreover, as therapists resonate with what they have received, they internally amplify the emotions connected with it (Schore, 2003a). They become very distressed without understanding why. They find it difficult to put into words what is going on.

For that reason, projective identification is considered a form of non-verbal communication. By placing the pain of being abused into their therapist, for example, clients enable their therapist to know by experience how painful it was for them to be abused. This is particularly important to clients when they cannot describe an experience. Consider the following vignette:

In his therapy session, the client denied being sexually abused. In fact, he laughed when he heard the suggestion that others with his symptoms usually have been sexualized at an inappropriate age. Yet his therapist experienced a vague, partly comfortable, partly uncomfortable sexual attraction to her client. It was not as if she perceived the client as physically attractive; it was simply an attraction “out there” by itself.

In time, when the therapist disclosed her countertransferential reaction, the client revealed that he had engaged in sexual play at age five with a babysitter. He enjoyed it, he said, even though he had no other fond memories of the person.

As the therapist and her client talked about what had occurred when he was a child, it became clear to her that what happened to her in therapy was an enactment. She realized that though her client said he enjoyed it, in fact he was conflicted over it. He enjoyed what he later learned he was not supposed to do. When he placed into his therapist his projective fantasy of having a sexual relationship with her, however, he could enjoy the memory of the original experience without having to own it.

Third, clients who are engaged in projective identification unconsciously attempt to recover the part they have expelled. They want to get the feel of what their therapist has gone through. They want to know what the expelled part is like now that the therapist has had to deal with it. They sense that their therapist has actually felt what they themselves could not tolerate and has not only tolerated it but also dealt effectively with it. As a consequence, the part is less terrifying, and their negative feelings are either gone or at least more manageable (Ogden, 1994). In the above vignette, for instance, the client would have sensed that that his therapist managed the sexual fantasy he had projected.

Thus by using projective identification, clients are able to fantasize

that they can safely take back or re-own their original experience. They will be able to benefit from their therapist’s modeling. They will be able to manage feeling controlled, for example, by rebelling against it, as did their therapist. Although negatively affected by a client’s projection, the therapist has managed to contain it (Pick, 1985).

14 Now, in a safe interpersonal environment, the client can “metabolize” a

negative emotion into something positive (Schore, 2003b).

It is not always the case, however, that therapists adaptively manage the feelings they have introjected. If they cannot tolerate them, they confirm clients’ belief that their feelings are indeed unbearable and unmanageable. Then clients feel even worse. They experience hopelessness and despair (Bion, 1967).

According to Grinberg (1962), who was among the first to link projective identification with countertransference, projective identification accounts for transference-countertransference enactment and role-responsiveness. Projective identification is a form of pressure exerted by clients to get their therapist to help them process affective experiences that they have not been able to deal with (Schore, 2003a). In that the therapist becomes as much an active participant as the client (Plakun, 1998), projective identification is interpersonal, rather than merely intrapsychic, as Melanie Klein (1946) conceived it.

A close look at introjective identification, an unconscious process whereby therapists experience a feeling state that clients have put into them in an attempt to disown it, reveals significant challenges for therapists. It takes one of two forms as therapists identify with what they have received and own it as their own.

In the first, called concordant identification, therapists feel like their client. They feel abused, for example, and sorry for the client who has been abused by her mother. The client’s subjective reality seems to the therapists to be based in their own current reality. Thus concordant introjective identification increases therapists’ empathy for their clients.

In the second, called complementary identification, however, therapists feel the impact of what the client has done to another person. They experience what the recipient of the client’s actions has experienced. As a consequence, they empathize not with the client but with the person with whom the client has interacted. To use the last example, the therapist experiences the frustration of the mother who resorts to abusing an obstinate child.

With this, there is good news and bad news. The good news is that the experience yields valuable information regarding what clients have contributed to their problems. The bad news is that therapists must now struggle with mysterious, unexplainable negative feelings toward their client. Unless they quickly process those feelings, they will enact them, giving their client additional psychic pain.

Even if concordant identification is therapists’ reaction, they cannot do psychological work for their clients. Being empathized with can mediate healing, but that healing will be temporary unless clients learn to heal themselves, which they can do if they face their pain, process it, and, in most cases, change what they do to prevent its reoccurrence. That might be refusing to accept victimhood as a fundamental self-identifying label for example, in the case of having actually been victimized and being victimized in the present.

In other words, only when clients become aware of the conflict inherent in transference and embark upon the hard work of conflict resolution can they free themselves from the pain of abuse.

15 That pain remains because the past becomes the present through a repetition

compulsion at the core of transference (Freud, 1912).

A Narrower Definition

Some theorists, such as Blum (1986a), find

countertransference’s totalistic definition so all-encompassing that it is

difficult to use in clinical settings. Consequently, they offer one that is

less comprehensive: countertransference is only those feelings and attitudes that

are unconscious, irrational, and inappropriate because they are displaced;

and it is only those that are conflictual or problematic.

If clients actually act badly in the

session and therapists get angry, that reaction is called a counter-reaction,

not countertransference. If, on the other hand, clients project onto therapists

an early-life “picture” of themselves as acting badly but do not actually act

badly in the session, and therapists introject that old “picture,” their angry

reaction is termed countertransference. Thus countertransference is

labeled irrational and inappropriate; it defies logic, strictly speaking. The present is not the past.16 One person is not another, however

much they resemble each other.

In other words, countertransference is a matter of the imagined or fantasized perceptions of which therapists are unaware. It is composed only of unconscious reactions.

Furthermore, countertransference involves only conflict-based reactions of therapists. If a therapist has resolved her

conflict over expecting her mother to meet her needs and finding her mother

instead neglectful, projection – but not countertransference – will occur. The

client who resembles a mother might project her own unresolved conflict related

to neglect, but the therapist will not feel neglected, at least not appreciably.

Descriptors of Countertransference

Whether defined classically or totalistically,

countertransference can be described in the following ways.

Countertransference Is Subtle

Though signs or manifestations of

countertransference are occasionally easily detectible, they are usually very

subtle. They tend to be disguised or vague feelings, desires, images, gestures,

fantasies, associations, bodily sensations, and urges to respond differently

from the way one usually does. They might take the form of silence, boredom,

fatigue, fragmentary thoughts, and various combinations of these phenomena

(Grayer & Sax, 1986). In response to a client who dislikes women, for

example, a female therapist might feel chest pains or have difficulty speaking.