Learning Objectives

This is an intermediate-level course. After completing this course,

mental health professionals will be able to:

- Discuss ethical and

legal considerations in providing information about medications to clients.

- Explain medication

treatment algorithms for depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, ADHD, and

bipolar spectrum disorders.

- Troubleshoot treatment-resistant

cases of depression.

- List experimental

treatments for treatment-resistant mental illness and the data supporting them.

- Describe the newest

treatments for postpartum depression.

The materials in this course are based on the most accurate

information available to the author at the time of writing and this course has been updated by Li Liang, MD. New developments in

the field of psychopharmacology occur each day and new research findings may

emerge that supersede these course materials. This course is updated regularly

as new practice guidelines are developed. This course will equip clinicians to

evaluate the needs for medical treatment for their psychotherapy clients, to

assess responses to treatment and to more effectively collaborate with primary

care physicians and psychiatrists.

Outline

- Introduction

- Preliminary

Considerations

- Legal and Ethical Issues

- Drug Metabolism and Medication Dosing

- The Process of Approving a New Drug by the FDA

- Depression

- Introduction

- A Changing Treatment Landscape

- Treatment Outcomes

- Abnormal Neurobiology: A Compelling Case for the Use of Antidepressants

- Diagnostic Issues

- Psychopharmacology of Depression

- Antidepressant Medications

- Pharmacologic Treatment Guidelines

- First-Line Medication Choices: Major Depression

- Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Treatment

Algorithm: Choosing a First-Line Antidepressant

- Partial and Non-Responder Strategies

- Phases of Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder

- Treatment for Other Types of Depression

- New Treatments and Interventional Treatment for Major

Depressive Disorder

- Herbs and Supplements for Major Depressive Disorder

- Combined Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy

- Bipolar Spectrum

Disorders

- Introduction and Diagnostic Issues

- Symptoms of Classic Mania

- Symptoms of Hypomania

- Symptoms of Mania or Hypomania with Mixed

Features

- Treatments for Bipolar Disorder

- Lifestyle Management

- Medication Treatments

- General Considerations

- What are Realistic

Outcomes?

- Bipolar Medications

- Other Medications We Can Use to Treat Bipolar

Spectrum Disorder

- Targets for Medication Treatment

- Getting Started with Medication Treatment

- Emergency Medication Treatments

- Laboratory Tests

- Treatment Guidelines

- Adjunctive Therapies for Bipolar Spectrum

Disorder

- Anxiety Disorders

- General Considerations

- Diagnostic Issues

- Psychopharmacology For Anxiety Disorders

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)

- Panic Disorder

- Social Anxiety

- Herbs and over-the-counter supplements

- Coffee and Anxiety

- Attention

Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- Introduction

- Diagnostic Issues

- Neurobiology

- Psychopharmacology of ADHD

- Appendix

- I. Psychiatric Medications: Quick Reference Guide

- II. Mood Stabilizers

- III. Anticonvulsant Mood Stabilizers

- IV. Antipsychotic Medications

- V. Antidepressant Medications

- VI. Antianxiety Medications: Benzodiazepines

- VII. Miscellaneous

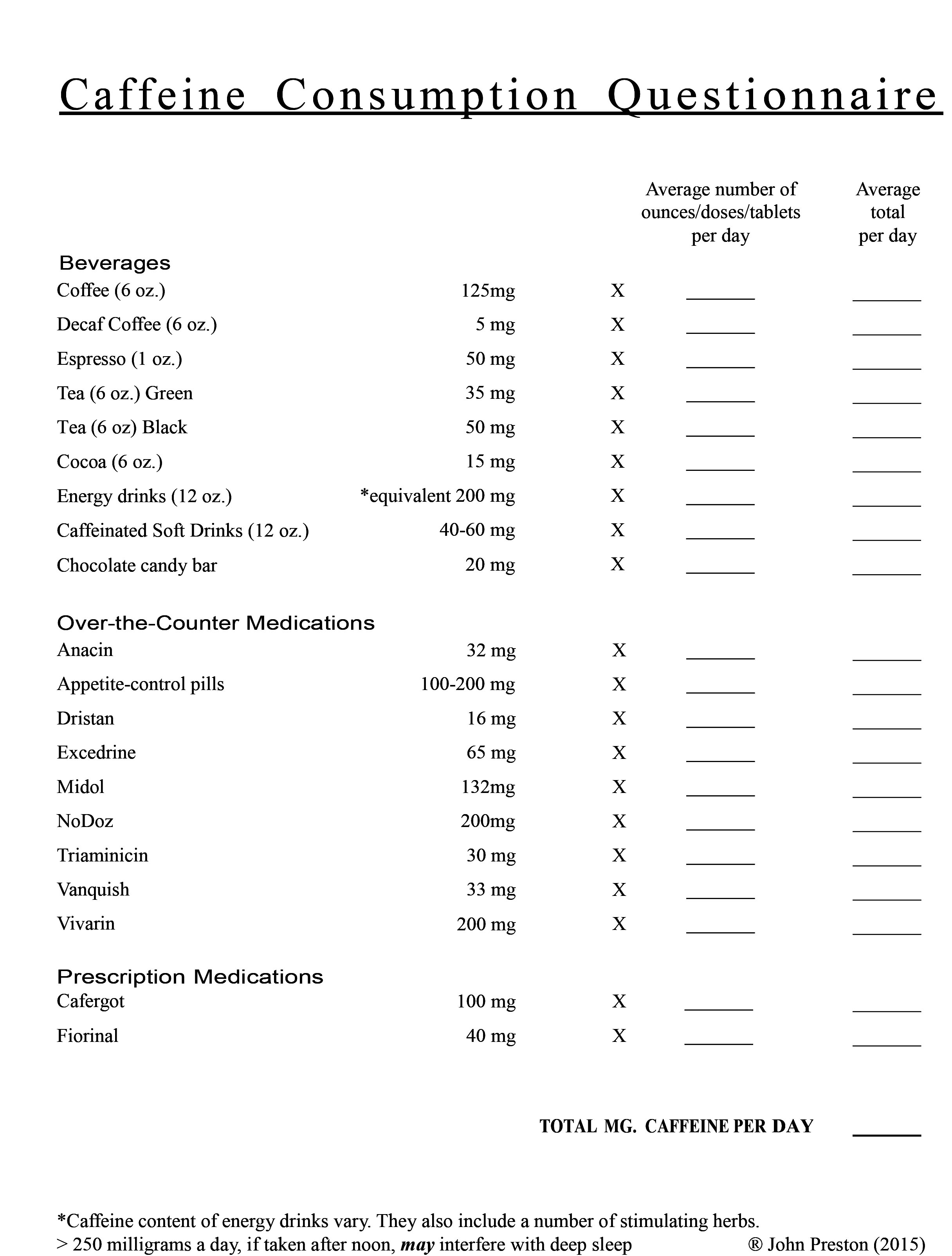

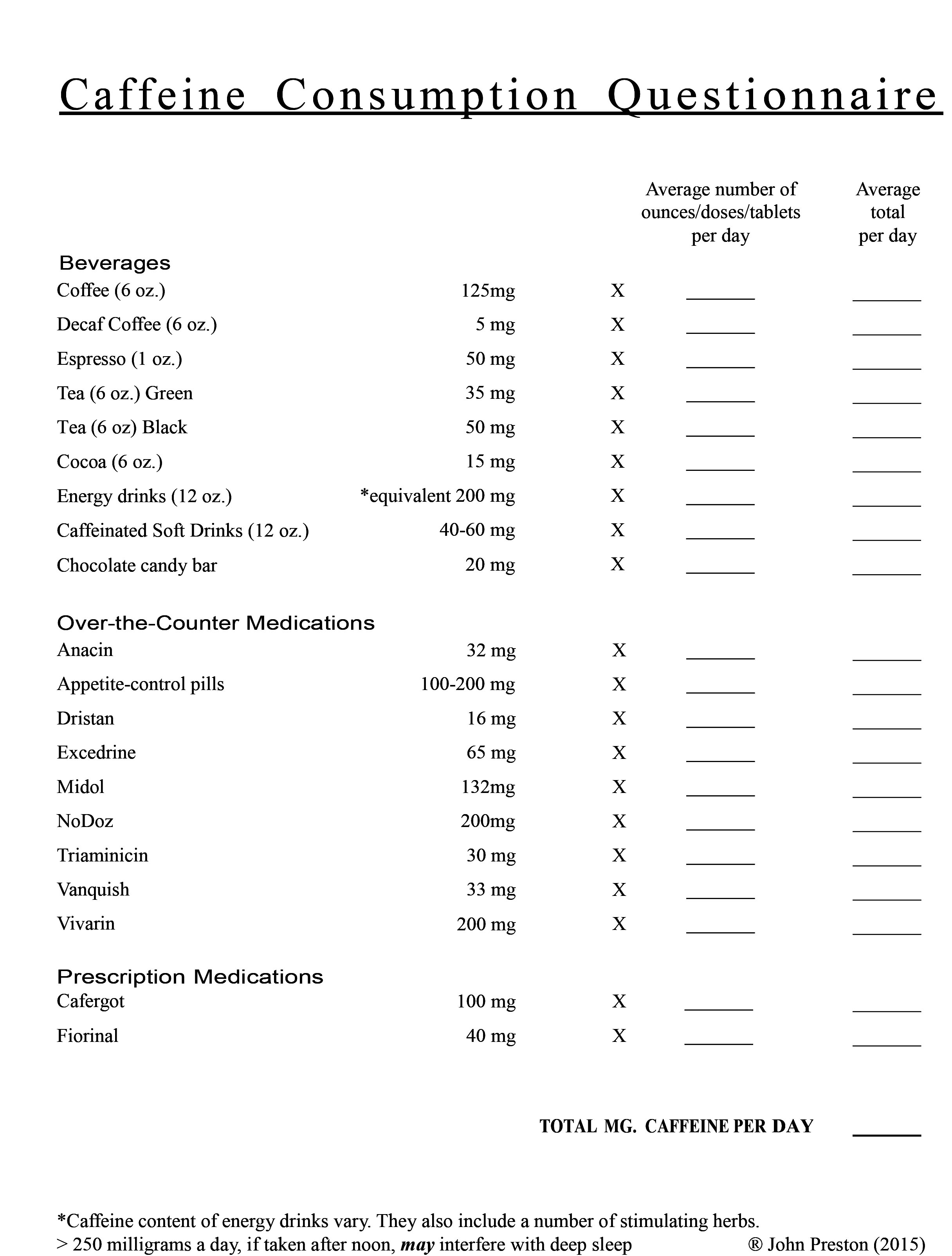

- VIII. Caffeine Questionnaire

- Suggested Readings/Resources

- References

Note: “Quick Reference to Psychiatric Medications” is

available as a free download on the following website. It is typically updated

once or twice a year. It may be helpful to have a copy of this as you read the

following material: apadivisions.org/division-55/councils/research/quick-reference.pdf.

Introduction

This course is designed to teach the

basics of clinical psychopharmacology for practicing psychotherapists. The

focus will be on three groups of commonly encountered clinical conditions: mood

disorders (depression and bipolar spectrum disorders), anxiety disorders, and

ADHD. An assumption is made that you are very familiar with psychopathology and

DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria, however there will be supplemental diagnostic

information presented in this course as it applies to treatment decision-making.

More recent epidemiological studies and new findings in the neurosciences have

influenced changes in some diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5-TR which will be

addressed in this course. In addition, there will be brief mention of

neurobiology and pathophysiology associated with certain clinical conditions,

although a comprehensive discussion of these topics is beyond the scope of this

course (see J. Cooper et al., 2003 and Preston et al., 2017 for a more

detailed review). The primary focus of this course is to provide a current

overview of psychopharmacologic treatment guidelines. Many of these are derived

from large-scale empirical studies (often referred to as algorithm studies).

Treatment guidelines do not represent personal opinions of the author, but

rather are presentations of algorithms that have been developed by NIMH-supported

programs, guidelines from the American Psychiatric Association, and the Texas

Medication Algorithm Project.

This is the first course in a three-course series. This first course teaches the basics of psychopharmacology. The second course, Bipolar Spectrum Disorders: Diagnosis and Pharmacologic Treatment, focuses on understanding common bipolar spectrum disorders and recognizing symptoms of mania, symptoms of hypomania, and symptoms of depression. The third course, Psychopharmacology for Child and Adolescent Mood Disorders: Problems and Promise, covers mood disorders in youth, including using psychotropic medication to treat youth.

All psychotherapists must be familiar with psychopharmacology for

three reasons:

- It is important to

know which classes of medication we use to treat different disorders so that

referrals can be made to an appropriate prescriber. It is a part of informed

consent to provide clients with information regarding all viable treatment

options for their particular disorder so that they can make choices about which

treatment to pursue.

- It is important to be

able to communicate clearly with physicians to whom our clients are referred to

share relevant information about the diagnosis and the client’s response to

treatment.

- In the current managed

care practice model, increasing numbers of clients are receiving psychiatric

medication treatment in their primary care physician’s office. Here the amount

of time spent with the physician may be very limited. Our clients often want

and need additional information regarding their medication treatment that is

not readily available from the primary care doctor. Psychotherapists can be

very instrumental in providing important information regarding such issues as:

side effects, how much time is required for medications to begin working,

realistic expectations for treatment outcomes with medications, etc.

Preliminary Considerations

Legal and Ethical Issues

A review of case law reveals a number of cases in which

non-physician health care professionals have been accused of practicing

medicine without a license because they gave patients information regarding

their medications and medical treatment. Obviously, it is important for all

therapists to practice within their scope of practice, to do whatever is in the

best interests of our patients and to be on solid ethical ground. It is clear

from the existing case law that it is unethical and illegal to tell patients

either: 1. to stop taking a medication, or 2. to change the dose of a

medication. This is considered practicing medicine. However, in every case

(with one exception addressed below) those who provided information regarding

medicines and medication treatment and were accused of practicing medicine

without a license were found to be not guilty. Further, in half of the cases, the

judge said that to not provide information to patients may have been acting in

a professionally incompetent manner.

Here is what this is based on. First and foremost is the right

granted by the first amendment, the right to free speech. Secondly, the

following are deemed appropriate to share with patients, if and only if the

therapist has training and is knowledgeable regarding the facts of medication

treatments:

- Once the diagnosis is

made, telling the patient about treatment options. This is a part of “informed

consent” in which the therapist must share with patients their available

treatment options – mentioning those treatments that are empirically supported.

Therefore, even if a therapist is not especially fond of pharmacological

treatments, it behooves them to share information regarding drug treatments. At

the heart of informed consent is a respect for our clients in terms of allowing

them to be the final judge in opting for certain treatments.

- Discussion about

medication side effects.

- Discussion regarding

the likely or common positive benefits of drug treatments (i.e., what kinds of

symptoms are likely to be improved with medications).

- Discussion regarding

the length of time that it may take for medications to begin to show clinical

effects.

- Limitations of

medication treatments.

- Underscoring the

importance of collaborative treatment, that is, the value in having both the

therapist and the prescribing doctor share information about the course of

treatment. For example, this communication might include amount of improvement, lack of improvement, emergent side effects.

- There is one case in

which a non-medical clinician was found to be unethical and this was due to the

fact that this person only recommended an over-the-counter product but failed

to talk about other available treatment options. As will be discussed below,

some over-the-counter products do have empirical support for efficacy in

treating some psychiatric disorders, and can be mentioned to patients as

options. However, this must be done in the context of presenting all available

empirically validated treatment options.

Due to the impact of managed care practice, as mentioned earlier, many patients are

receiving prescriptions for psychotropic medications from primary care

physicians who may have very limited time to spend with the patients both initially,

when the diagnosis is made and treatment is initiated, and in follow-up. This

is a significant problem and psychotherapists can provide enormous help to

patients by monitoring their response to medication and providing

support and information regarding drug treatments, and they should be able to

do so in ethical and legal ways. Ultimately, the care of our patients is

paramount.

Drug Metabolism and Medication Dosing

For each psychiatric medication discussed in this text, you will

see listed the typical adult daily doses. In many instances the “therapeutic

dosage range” is broad. For example, daily dosing with lithium is between 600

and 2,400 mg. or for Prozac, 10 to 80 mg. per day. It is important to know that

the amount of medication required to effectively reduce and eliminate symptoms

often has little to do with how severe the symptoms are. And what matters is

not so much how much drug is ingested but rather, how much of the medication

enters the blood stream.

There are three primary factors that influence the amount of drug

that finds its way into the blood stream. First is the rate of liver

metabolism. Psychotropic medications are absorbed through the walls of the

stomach and intestines and go directly to the liver. Here the drug molecules

are acted upon by liver enzymes that begin a process generally referred to as

biotransformation. Liver enzymes chemically alter the medication in ways that either

activate the medication or allow the drug to be more readily excreted from the

body. The liver’s function is to detoxify the body. Thus, in this so-called

“first pass effect” through the liver, a good deal of the drug is chemically

transformed and then rapidly excreted from the body. However, some of the

medication initially escapes this process and makes its way through the liver

and into circulation, and thus is allowed to begin accumulating in the bloodstream.

How rapidly the liver metabolizes drugs depends on a number of factors. This

resulting blood level is what matters when it comes to reducing symptoms.

(Note: two psychotropic medications are not metabolized in the liver: lithium

and Neurontin).

Genes play a significant role in this process. A small percentage

of people are known as rapid metabolizers. They take certain drugs and then

eliminate them very quickly. The result is that even though they may be taking

what seems like an adequate dose of the medication, little actually gets into

the blood stream. Once it is discovered that someone is a rapid metabolizer, it

is usually required that they be prescribed higher doses of medications and

eventually enough gets into the bloodstream to be effective. Again, this has

nothing to do with how severely ill they are … it’s just a matter of the

liver’s metabolic rate.

Converse to this are the hypo-metabolizers. This also small

percentage of people (perhaps 5% of the general population) have fewer

than average liver enzymes. It is important to note that those of Asian and

African descent show higher percentages of hypo-metabolism, approximately 33%,

and thus more caution should be taken with initial dosing in these individuals

to avoid significant side effects. The effect is that they can take a “typical”

starting dose of a medication, and on its trip through the liver, only small

amounts are transformed and excreted. The result is often very high blood

levels of the medication and severe side effects or toxicity. Thus the ultimate

solution for hypo-metabolizers is to use very small doses of medications

initially and then increase doses gradually. Sometimes when a person is first treated,

they will experience serious side effects and this may be due to

hypo-metabolizing. It is often hard to know ahead of time if this will happen

with any one given individual. Thus, if your patient has had an experience of

encountering very intense side effects with other medications in the past, one

may anticipate that they may be a hypo-metabolizer, and thus initial dosing

should be low and increased dosing should be done gradually.

A second factor determining blood levels of medications is the

functioning of the kidney. Sometimes genetic factors play a role here too, but

more often problems can occur due to kidney disease. Thus, for some bipolar

medications in particular, pretreatment laboratory testing will include an

assessment of kidney functioning. This is especially important for patients

being treated with lithium; it eliminates without metabolism and is excreted by

the kidney.

Finally, a number of drugs can adversely affect liver metabolism

and thus alter blood levels. Here is where drug-drug interactions can cause

significant problems. This applies to some prescription drugs, over-the-counter

drugs, herbal and dietary supplement products, and recreational drugs. The use

of prescription drugs must be carefully monitored by the treating prescriber.

In addition, even modest amounts of alcohol can have significant effects on the

liver. St. John’s Wort, a popular herbal product for the treatment of

depression, is well known for causing some very significant changes in liver

metabolism.

The Process of Approving a New Drug by the FDA

There are four steps to getting a new drug approved by the FDA.

The pharmaceutical company has created a new chemical compound and done the preclinical

toxicology studies; then they have to submit an investigation of new drug

application (IND) to the FDA, followed by three phases of clinical trials. The FDA

will approve the final new drug application (NDA) based on the clinical trial

data. The FDA also monitors the post-market drug safety. (Drugs.com)

- Phase 1 focuses on safety. About 20 to 80

healthy volunteers are needed to establish a drug’s safety and profile,

and it takes about one year to complete. Safety, metabolism, and excretion

of the drug are also emphasized.

- Phase 2 focuses on effectiveness. Roughly 100 to

300 patient volunteers are required to assess the drug's effectiveness in

those with a specific condition or disease. This phase runs about two

years. Groups of similar patients may receive the actual drug compared to

a placebo or other active drug to determine if the drug has an effect.

Safety and side effects are reviewed.

- Phase 3 studies begin if evidence of

effectiveness is shown in Phase 2. Typically, several hundred to 3,000

patients are monitored in clinics and hospitals to carefully determine

effectiveness and identify further side effects. The manufacturer may look

at different doses as well as the experimental drug in combination with

other treatments. This phase runs about three years on average.

- Phase

4 studies gather additional information about a product's safety, efficacy,

or optimal use after approval. Post-marketing studies may take place in

groups of patients who are using the drug in a real-world setting. These

studies may identify additional uses, long-term effectiveness, and

previously undetected side effects. Rare side effects that occur in fewer

than 1 in 5,000 patients are unlikely to be seen in Phase 1 to 3 studies

before approval, but groups of patients this large are not usually studied.

These rare side effects are more likely to be found when large numbers of

patients use a drug after it has been approved and marketed.

Depression

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) has launched the comprehensive

Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2030. Depression is a common mental illness; it

can affect anyone. Globally an estimated 3.8% of the population experience depression,

including 5% of adults (4% among men and 6% among women), and 5.7% of adults

older than 60 years. Approximately 280 million people in the world have

depression.(1) Depression is about 50% more common among women than among men. Worldwide, more

than 10% of pregnant women and women who have just given birth experience

depression.(2) More than 700,000 people die due to suicide every year. Suicide is the fourth

leading cause of death in 15-29 year-olds.

The twelve-month prevalence of major depressive

disorder in the United States is approximately 7%, with marked differences by

age group such that the prevalence in 18-29 year-old individuals is three times

higher than the prevalence among individuals age 60 years or older. Depression is the leading cause of

disability in the United States for individuals age 15-44 (DSM-5-TR), and ranks as the second most commonly seen

disorder in patients seeking treatment from primary care physicians. Data shows

the prevalence increased in the United States from 2005 to 2015 with steeper rates

of increase for youth compared with older groups. Non-hispanic whites showed a

significant increase. Morbidity and mortality associated with serious mood

disorders is enormous. Chronic and recurrent depressions significantly increase

risk for coronary heart disease, stroke, and osteoporosis (NIMH, 2003).

It is estimated that only 50% of those in the United States who

suffer from major depression seek treatment. Additionally, treatment received

is often very inadequate. In the United States most drug treatment for

depression takes place in primary care medical settings. Eighty-five percent of

prescriptions written in the United States for antidepressants are written by

physicians and nurse practitioners and physician assistants who do not have

specialty training in psychiatry. This is due in large part to managed care’s

efforts to cut costs by having the majority of psychiatric treatment take place

in primary care settings. In addition, there are shortages of psychiatrists.

Treatment outcomes in primary care medical settings may have poor response largely

due to the lack of adequate follow-up.

A Changing Treatment Landscape

The 1980s and 1990s saw the proliferation of HMOs and managed care

companies that attempted to streamline mental health care in order to achieve

cost containment. During this same time psychiatry training programs have

increasingly emphasized psychopharmacology as the mainstay of treatment for

clinical depression. Finally, pharmaceutical advances and marketplace forces

have had a substantial impact on shifting patterns of practice in the mental

health arena away from psychotherapy.

In many settings, psychotropics have become the primary or sole

form of treatment for many suffering from serious mood disorders. Yet, the vast

majority of patients treated either do not respond or only experience partial

responses.

Treatment Outcomes

How effective are antidepressants? All drugs must go through

rigorous trials prior to FDA approval, and must demonstrate clear superiority

over placebos. The currently available antidepressants have all passed the

test, but the outcome data is often spurious and plagued by methodological

flaws. First and foremost, in the majority of pre-FDA-approval efficacy studies,

patients selected for medication trials hardly resemble typical outpatient

populations. Patient selection excludes those who have had prior suicide

attempts, who have psychotic or bipolar symptoms, and who have comorbid medical

illnesses, or substance use or personality disorders. A paper by Zimmerman,

Posternak, and Chelminski (2002) looked at consecutive patients seen in an

outpatient setting who were diagnosed with unipolar/major depression. If

patient selection criteria as noted above were applied to this typical group

of depressed outpatients, 85% of them would be excluded from drug trials.

Complex comorbidity is the rule, not the exception, in usual clinical settings.

Thus, it may not be appropriate to generalize results from efficacy studies to

the real world of clinical practice.

Another significant flaw in the reporting of outcome data is the

common practice of excluding dropouts due to side effects from percentages of

responders (Gitlin, 2002). Thus, for most antidepressants studied, the positive

outcomes are inflated (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Antidepressant Treatment of Major Depression Outcome Results:

General Results Reported from Drug Efficacy Studies |

|

Commonly Reported Outcomes |

ITT Outcomes* |

Side-effects drop-outs |

15% |

15%** |

Responders |

60% |

50% |

Non-Responders |

40% |

35% |

*ITT: intention

to treat ** Drop-out rates due to side effects vary among new generation

antidepressants ranging from Wellbutrin, SR: 9%, to Paxil: 21%. |

A

large-scale clinical trial funded by the National Institutes of Health aims to

address whether antidepressants work or not. The Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve

Depression (STAR*D) study is the largest prospective clinical trial of major

depressive disorders ever conducted. It was a multicenter, nationwide

association of 14 university-based regional centers, which oversaw a total of

23 participating psychiatric clinics and 18 primary care clinics. Enrollment

began in 2000, with follow-up completed in 2004. All enrolled patients began on

a single selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) (citalopram) and were

managed by clinic physicians who followed an algorithm-guided acute phase treatment

through five visits over a 12-week course. Dosing was aggressive and focused on

maximizing the tolerable dose; if patients who were tolerating a medication had

not achieved remission (that is, complete recovery from the depressive episode)

by any of the critical decision points (weeks 4, 6, and 9), the algorithm

recommended increasing the dose. Patients whose depression did not remit after

this initial treatment were able to participate in a sequence of up to three

randomized clinical trials or levels. The results do show antidepressants work,

but with limitations, and it requires a combination of medications along with

cognitive therapy to achieve better clinical outcome. (Rush, et al., 2006)

What has become clear is that mood disorders are tremendously complex and heterogeneous disorders that involve numerous interacting variables, such as, genetic predisposition, underlying medical and neurobiological changes, life stressors, interpersonal relationships, and intrapsychic, cultural, and existential features. It is the appreciation of such complexity that has led to increased interest in integrative approaches to treatment (Preston, 2006).

Abnormal Neurobiology: A Compelling Case for the Use of

Antidepressants

A comprehensive review of the neurobiology of depression is beyond

the scope of this paper. However, let us consider a few important research

findings that have emerged during the past decade. Sixty percent of people

experiencing a major depressive episode exhibit a hyperactive

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) neuroendocrine axis (see Figure 1). In

mammals, when danger or adversity is perceived in the environment, a number of

complex events take place in the nervous system, launching adaptive

fight-or-flight responses. One of the most important components of this

biological response is the activation of the HPA axis, which ultimately

releases glucocorticoid hormones into general circulation. In humans, the principal

glucocorticoid is cortisol. Cortisol operates to facilitate the release of

glucose into the blood stream and to increase blood pressure, both of which are

essential for mounting an effective fight-or-flight response.

Figure 1.

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Neuroendocrine Axis

See also, Le Doux (2015)

Hypo: Hypothalamus, CRF: corticotropin

releasing factor, PIT: pituitary gland, ACTH: Adrenocorticotropic hormone.

Cortisol enters circulation and is distributed throughout the

body. In the brain, the most prominent site for cortisol response is the limbic

brain structure, the hippocampus. In adaptive fight-or-flight responses,

cortisol activates the hippocampus to inhibit the HPA axis, operating like a

“brake”. Of course, if danger persists in the environment, the HPA axis is

continuously reactivated. However, when stressors subside, the

cortisol-mediated feedback loop shuts down the system, and thus plays a role in

affect regulation (LeDoux, 2017).

This hyperactivity of the HPA axis, seen in many cases of major

depression, results in a condition known as hypercortisolemia. Here,

cortisol levels are significantly elevated and have been shown to be

neurotoxic. These high, sustained, toxic levels of cortisol have a marked

impact on hippocampal nerve cells (e.g., causing dendrite retraction, cell death, and hippocampal atrophy). Hypercortisolism also may damage other neural tissue including the anterior cingulate, amygdala, and cerebellum, all of which have been

implicated in playing a role in affect-regulation). Over time, the result is

progressive brain damage that likely accounts for the deteriorating course seen

in many cases of untreated or poorly treated recurrent and chronic depression

and bipolar illness (Sapolsky, 1996). High cortisol levels in depressed

pregnant women cross the placental-blood barrier and may adversely affect the

fetus’s nervous system.

Additionally, depression reduces the gene expression of brain-derived

neurotropic factor (BDNF), which is a neuroprotective molecule known to

facilitate the repair of damaged nerve cells and to promote neuron regeneration,

that is neurogenesis, in the hippocampus. Molecular studies have also implicated

peripheral factors, including genetic variants in neurotrophic factors and

pro-inflammatory cytokines. Additionally, volumetric and functional magnetic

resonance imaging studies provide evidence for abnormalities in specific neural

systems supporting emotion processing, reward seeking, and emotion regulation

in adults with major depression (APA, 2022).

Antidepressant medications reduce cortisol levels (Heim &

Nemeroff, 2002; Nestler, Hyman, & Malenka, 2001) and reactivate the

production of BDNF, which can lead not only to clinical improvement, but also

to the birth of new nerve cells in the hippocampus (Kempermann

& Gage, 1999) (note: lithium, Depakote, Tegretol, Lamictal, Seroquel, and

Equatro, and regular exercise also increase the levels of BDNF). In this

way, antidepressants can play a crucial role in treating symptoms of depression

as well as protecting the brain from the effects of toxic levels of stress

hormones.

Diagnostic Issues

For many years, a distinction was made between so-called “reactive

depressions” or “psychological depressions” (by definition, depressions that

emerged in the wake of significant psychosocial stressors) and “endogenous

depressions,” presumably due to the effects of certain changes in neurobiology, such as,

genetically based mood disorders, secondary to various medical illnesses such as thyroid disease, or due to the impact of substances(e.g., alcohol or antihypertensive drugs). Currently, the distinction between endogenous and reactive depressions is less relevant. The critical diagnostic issues, as this relates to the decision to treat with antidepressants, include the following:

1. Marked dysfunction

(social, occupational, etc.) that lasts for more than two weeks or fails to

respond adequately to psychotherapy.

2. Depressed/sad mood and/or

loss of interest in life. Feeling hopeless, helpless, and/or worthless most days

or every day for at least two weeks.

3. Patients who are of

below-average intelligence, are significantly non-psychologically minded (i.e.,

unable to introspect), who refuse psychotherapy, where professional treatment

is not available, or who are too impaired to productively participate in

psychotherapy.

4. The presence of

neurovegetative symptoms (if these are sustained, i.e., present most days):

- Sleep disturbances (especially early morning awakening and

middle insomnia);

- Loss of libido;

- Anhedonia or a non-reactive mood;

- Appetite and weight changes (either increased or decreased);

- Marked fatigue;

- Psychomotor retardation or agitation; or

- Diurnal variations in mood and cognitive ability,

generally, more pronounced in the morning.

5. 66% of patients with Persistent

Depressive Disorder (previously called dysthymia) have been shown to be

responders to antidepressants and thus should also be considered for such

treatment.

6. Depression is caused

by a general medical condition or prescription medications. Typically, the

treatment strategy is to focus treatment on the general medical condition

directly and only use antidepressants if such treatment is unable to resolve

the depression. Likewise, a change in prescription medications (e.g., changing

the type of antihypertensive medication used to treat high blood pressure to a

different class of antihypertensive) may be effective in reducing depressive

symptoms. However, if not, the addition of an antidepressant may be considered.

7. Substance/Medication-induced

depression disorder. The essential character of substance/medication-induced

depression is directly due to physiological effects of a substance (e.g., a

drug of abuse, a medication, or a toxin exposure). We can do laboratory testing

(blood test and/or urine test) to detect a substance. The treatment goal is

absence from substance use or stopping the medication that can cause

depression. We can use an antidepressant to treat depression as well.

Psychopharmacology of Depression

Antidepressant Medications

Antidepressants and their daily adult dose ranges are listed below.

These medications have been developed since the late1980s and are considerably

safer and easier to tolerate than older-generation tricyclic and MAOI

antidepressants. The following table lists the commonly used antidepressants

from the different classes.

Classes of Antidepressants |

Generic Name |

Brand Name |

Typical Adult Daily Dose |

SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) |

fluoxetine |

Prozac, Sarafem |

10-80 mg |

| |

paroxetine |

Paxil/Paxil CR |

20-50 mg |

| |

citalopram |

Celexa |

20-40 mg |

| |

escitalopram |

Lexapro |

10-20 mg |

| |

sertraline |

Zoloft |

50-200 mg |

| |

fluvoxamine |

Luvox |

50-300 mg |

SNRIs

(serotonin norepinephrine

reuptake inhibitors) |

venlafaxine |

Effexor/Effexor XR |

37.5-225 mg |

| |

duloxetine |

Cymbalta |

20-120 mg |

| |

desvenlafaxine |

Pristiq |

50-100 mg |

| |

levomilnacipran |

Fetzima |

20-120 mg |

TCAs (tricyclic antidepressants) |

amitriptyline |

Elavil |

25-300 mg |

| |

nortriptyline |

Pamelor |

25-150 mg |

| |

clomipramine |

Anafranil |

25-250 mg |

| |

sinequan |

Doxepin |

25-300 mg |

| |

impramine |

Tofranil |

25-100 mg |

MAOIs (monoamine oxidase inhibitors) |

phenelzine |

Nardil |

45-90 mg |

| |

selegiline |

Emsam (patch) |

6-12 mg/24h |

| |

tranylcypromine |

Parnate |

30-60 mg |

Atypical

antidepressants |

bupropion |

Wellbutrin (SR/XL) |

150-450 mg |

| |

mirtazapine |

Remeron |

15-45 mg |

| |

trazodone |

Desyrel |

100-300 mg |

| |

vilazodone |

Viibryd |

10-20 mg |

| |

vortioxetine |

Trintellix |

5-20 mg |

| |

dextromethorphan/bupropion |

Auvelity |

45/105 mg (two tabs daily) |

Pharmacologic Treatment Guidelines

During the past 20 years, large-scaled empirical studies have been

designed in order to establish guidelines for what is currently referred to as

“evidence-based medicine”. These include the STAR-D (Sequenced Treatment

Alternatives for Relieving Depression: a multi-site study sponsored by the

National Institute of Mental Health), the Texas Medication Algorithm Project,

and UCLA’s Targeted Treatment for Depression Program (Metzner, 2000). Treatment

guidelines in psychiatry have been influenced by three factors:

1. Marketplace variables,

such as pharmaceutical company advertising and decisions made by HMOs and managed

care companies to adopt cost-effective drug formalities).

2. Consensus, that is,

inviting “experts” to convene a panel and discuss pros and cons of various

medical treatments and agree upon best treatment strategies, and

3. Results

from a large amount of research regarding treatment outcomes. The latter of

these offer important information, but may be inherently flawed because most

psychopharmacology outcome studies are sponsored by drug companies who have a

vested interest in producing good outcomes. The major drawback here is that

many null studies never make it into the journals. Thus, it is difficult to

realistically evaluate the effectiveness of certain treatments with only

primarily positive outcome data available.

The large-scaled studies mentioned above are funded by the NIMH,

Texas Department of Mental Health, and a university, respectively, and thus may

more accurately reflect realistic outcome data, not influenced by the profit

motives of drug companies. Also, the studies are not ones of consensus

opinions, but rather based on empirical outcomes with very large groups of

subjects.

What is summarized below are the first of what promises to be a

growing body of evidence-based data that can suggest specific strategies for

the treatment of major depression.

First-Line Medication Choices: Major Depression

(Metzner, 2000; Shelton & Tomarken, 2001; Goodwin & Jamison,

2007).

Major depression as defined by DSM-5-TR criteria represents a

heterogeneous group of mood disorders that vary in terms of severity (mild to severe),

clinical/symptomatic presentation, and presumed etiology. A large body of

neuroscience research has strongly implicated that dysregulation of certain

central neurotransmitters may be associated with particular

psychiatric symptoms. Most individuals who experience a decreased availability

of neurotransmitters such as serotonin (5-HT), dopamine (DA), or norepinephrine

(NE) do not develop clinical depression (Delgado, Charney, Price, et al.,

1990). However, some do, which is likely due to underlying genetic or other

vulnerability factors. Among depressed subjects, inadequate functioning of

5-HT, DA, or NE can contribute to certain core depressive symptoms such as a

depressed mood, pessimistic and negative thinking, guilt, low self-esteem, and

fatigue. What has emerged during the past two decades of research are general

but consistent findings suggesting that beyond common core symptoms of

depression, particular neurotransmitter dysfunctions may be accompanied by, or

cause, specific symptoms:

- Serotonin

Dysregulation: irritability, impulsivity, suicidal impulses/behavior,

ruminations;

- Dopamine and/or

Norepinephrine Dysregulation: apathy, anhedonia, low motivation.

Closely paralleling these findings from neuroscience research are

data from empirical pharmacologic studies (e.g., Metzner, 2000), which have led

to the following guidelines in which particular symptomatic features point

toward first-line antidepressant medication choices.

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Treatment Algorithm: Choosing a

First-Line Antidepressant

In general, medications recommended for major depressive disorder include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, which are used as the first-line treatment: Prozac, Zoloft, Paxil, Luvox, Celexa, and Lexapro. However, one-third to two thirds of depressed patients do not respond satisfactorily to their first antidepressant (Li et al., 2021) . SNRIs can be used as the second-line choice (serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors such as Effexor, Pristiq, Fetzima, and Cymbalta) Because 15% to 40% do not respond to several antidepressants, the underlying cause of depression is not a simple answer (Li et al., 2021).

Antidepressants may have a side effect referred to as activation (affecting approximately 10% of patients), which is experienced as increased energy, anxiety, initial insomnia, and/or agitation, typically emerging several hours after taking the first dose (also this can occur shortly after dose escalations). In individuals with this acute onset, side effects often result in abrupt patient-initiated discontinuation (the side effects often scare patients and may make them very reluctant to go through another antidepressant trial).Thus although after 4-6 weeks of treatment SSRIs often begin to significantly reduce both depression and anxiety symptoms, the initial few weeks of treatment can be very challenging and many patients drop out of treatment. A popular and effective way to address this problem is to initially co-administer an anti-anxiolytic agent, such as a benzodiazepine (e.g. Ativan, a minor tranquilizer) to rapidly reduce anxiety, agitation, and drug-induced activation. In addition, since benzodiazepines begin to reduce anxiety within an hour of taking the medication, the experience for many patients is that they feel noticeably better, quickly. This is an added benefit because it often leads to hopefulness about treatment and enhances compliance. Generally, after one month of treatment the benzodiazepine can be phased out. This is often a very successful strategy, however there is one important warning. Since benzodiazepines can be drugs of abuse, the use of these agents is risky and not indicated if there is a history of alcohol or substance abuse. With an addiction history, some psychiatrists are now using the non-habit-forming antihistamine, hydroxyzine (Atarax; Vistaril), to target the activation, or low doses of trazodone (25-50 mg), or low-dose Remeron (7.5-15 mg) for initial insomnia. We can combine the dual-action antidepressants such as SSRIs with Wellbutrin or SNRIs with Wellbutrin to target different neurotransmitters, i.e., targeting 5-HT, DA and NE, and DA and 5-HT respectively. If the patient has only a partial response to an antidepressant, we can use an augmentation strategy to achieve a better result.

If a patient has major depressive disorder with psychotic

features, we can add an antipsychotic medication as an adjunctive treatment to

manage psychotic symptoms.

If a patient’s depression is very severe – the patient is unable

to eat, sleep, or function – the ECT treatment can result in up to 80% symptom reduction.

For patients who have atypical depression, symptoms

include: hypersomnia, appetite increase, carbohydrate craving with subsequent

weight gain, and severe fatigue. Other symptoms often associated with atypical

MDD are rejection sensitivity and anxiety attacks. Medications of choice are

SSRIs, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) and possibly Wellbutrin.

It is important to exercise caution when treating atypical MDD

because many such individuals may be expressing the depressive phase of bipolar

illness and if treated with antidepressants alone there is a risk of switching

(i.e., provoking mania or hypomania) or cycle acceleration (the tendency to

cause increasingly severe or more frequent mood episodes). It has been found

that 80% of those suffering from atypical depression ultimately are discovered

to have bipolar disorder (usually, bipolar II). More will be said about

switching and cycle acceleration in the section below on bipolar illness.

Partial and Non-Responder Strategies

Clinically, 55% to 65% of patients treated with antidepressants only experience a partial response or no response at all when receiving their first antidepressant trial (Paykel et al., 1995; Doraiswamy et al., 2001; NIMH: STAR-D, 2008). And as noted earlier, those who do not reach full remission incur an increased risk of relapse (Paykel et al., 1995). STAR*D has shown that 50% of patients will achieve remission if they stay on the treatment after two treatment steps (Rush et al., 2006). Empirical studies are beginning to provide databased treatment guidelines for partial or non-responders (see Texas Department of Mental Health, 2005 and NIMH: STAR-D Program, 2008).

It must first be recognized that a number of factors may account

for less than adequate antidepressant responses, including the following:

- Excessive use of

caffeine or energy drinks that can significantly interfere with slow-wave

(deep) sleep which can aggravate depression;

- Unreported substance

abuse (in particular, alcohol use/abuse which may both exacerbate depressive

symptoms and interfere with the metabolism of antidepressant medications);

- Unsuspected medical

illnesses (e.g., sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, or thyroid disease);

- Failure to address key

psychological conflicts and/or family-based psychopathology;

- Choice of wrong class

of antidepressant medication (e.g., pharmacologically targeting the serotonin

system when in fact a particular patient’s depression is associated with

dysregulation of norepinephrine); and

- Chronic residual brain

impairment sustained during previous untreated or inadequately treated depressive

episodes (due to hypercortisolemia).

Partial Responder Strategies The highest yield next step

strategy is to progressively increase the medication dose (Trivedi & Klieber, 2001). This was also born

out in the STAR-D program that demonstrated better outcomes for very ill and

treatment-resistant cases by using high doses of antidepressants. Some patients

who are hyper-or rapid metabolizers require higher doses to achieve adequate

blood levels. The doses can be progressively increased if tolerated. If this

strategy is ineffective or impossible owing to emergent side effects, step two

is to augment (that is, to add an additional medication to the current drug).

Augmentation strategies often yield good responses in 35%-65% of those treated.

The following are common augmentation strategies that

often are successful:

- SSRI plus atypical

antipsychotic. Note: this strategy is often successful in treating partial

responders who have major depression with/without psychotic features. There

are four FDA-approved medications for augmenting antidepressants in the

treatment of major depression. They are Abilify, Rexulti, Seroquel XR, and

Vraylar;

- Antidepressant plus

lithium (generally lithium levels of 0.4-0.6 mEq/l);

- Antidepressant plus T3

(triiodothyronine), 25-50 micrograms per day;

- Combining Effexor and

Remeron (Stahl, 2000); and

- Antidepressant plus Transcranial

Magnetic Stimulation (TMS).

Non-Responder Strategies Once again, one must evaluate

issues involving adherence and possible substance abuse. Another consideration

is to make sure the diagnosis is major depressive disorder. Should these issues

be ruled out, then the highest yield next step strategy is to optimize the dose

(dosage increases, if tolerated). Should a high dose be reached and there is

still little or no response, then the next-step strategy is to change classes

of medications (e.g., switch from a serotonin-active drug [SSRI], such as Zoloft,

to a different class of antidepressants. (Trivedi & Klieber 2001).

Phases of Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder

There is general agreement among research groups that the

treatment of major depression involves three phases (American Psychiatric

Association, 2003; Texas Department of Mental Health, 2003):

Acute Phase:

Starts with the first dose and extends until the patient is asymptomatic. Since

symptoms have abated, many patients will naturally think that they no longer

need medications and will discontinue (against medical advice). At this point

in treatment, should patients discontinue, more than one-half will experience

an acute relapse within a few weeks (Stahl, 2013). Ongoing antidepressant

treatment, however, decreases the likelihood of acute relapse, necessitating

the next phase.

Continuation Phase: Continue treatment at the same dose for a

minimum of six months. If during this time period there are no breakthrough

depressive symptoms, then discontinuation can be considered. Gradual

discontinuation over a period of six weeks is strongly recommended to

avoid discontinuation withdrawal symptoms.

Maintenance Treatment: Lifelong treatment is strongly indicated for patients with

highly recurrent major depressions, those in their third or subsequent

episodes. Chronic treatment in an attempt to prevent recurrence can be helpful

in this regard as we manage other chronic illnesses such as hypertension and

diabetes. The maintenance of treatment is essential to prevent recurrence of depression.

Treatment for Other Types of Depression

Seasonal Depression: This often responds to high-intensity light therapy, generally

provided by the use of a commercially available light box or going out-of-doors

without sunglasses. The typical “dose” of light therapy is 10-30 minutes of

exposure to a light source that emits a minimum of 10,000 lux. The light has an

impact by striking the retina, which activates a specific nerve pathway (the

retinal-hypothalamic nerve). In most cases, high-intensity light therapy must

be accompanied by the use of antidepressant medications (Rosenthal, 2013). Note

that some seasonal mood disorders are associated with bipolar illness and thus

one must exercise caution in using bright light therapy to prevent a shift into

mania.

Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD): This disorder is characterized by repetitive cyclical,

physical, and behavioral symptoms occurring in the luteal phase of the normal

menstrual cycle. Symptoms may extend into the first few days of menses. Mood

symptoms are only seen for discrete periods of time prior to menstruation and

absent the rest of the month. The low-dose SSRI or SNRI is often helpful if the oral contraceptive or other alternative therapies, exercise or change of diet fail to control the symptoms. A higher dose may be prescribed if there is no response.

Postpartum Depression: Clinically, one in eight women

experience symptoms of postpartum depression, and the rate of depression

diagnosed at delivery is increasing. Technically, this can occur during

pregnancy but more commonly occurs after the birth of the infant. Especially if

there is a pre-existing depression, the onset can follow rapidly after

delivery. However, more commonly, the average onset is within four weeks

following delivery. Postpartum depression is distinct from what is often

referred to as “the baby blues”. Such a condition is not pathological but

rather reflects increased emotional sensitivity in general, for the full range

of emotions, including happiness as well as bouts of sadness or tearfulness.

It is thought that this phenomenon, common to most new mothers, occurs in 30%

to 80% of women following childbirth, with symptoms developing within two to three

days after delivery, peaking on the fifth day, and resolving within two weeks.

Postpartum depression, however, is quite different, with a prolonged

course and more severe symptoms. It often presents with symptoms of depressed mood,

anhedonia, weight changes, sleep disturbance, psychomotor problems, low energy,

excessive guilt, loss of confidence or self-esteem, poor concentration or

suicidal ideation. Many women tend to experience a severe episode and are

completely unable to hold or are disinterested in holding their babies. This

can profoundly interfere with critical early child-mother bonding (consequences

that may have a life-long impact). The greatest risk is postpartum psychosis.

Here, mothers do not interact at all with their children and in many cases,

they include the child in their delusional thinking. Estimates show that each

year in the United States 150 babies are killed by their mothers in the midst

of florid psychotic thinking and behavior. All women with postpartum psychosis

should be strongly considered for hospitalization.

The treatment is psychotherapy and/or medication. Antidepressants are recommended for more severe episodes. Response rates are slow and such depressive and psychotic symptoms, if untreated, last longer than most unipolar depressive episodes. They may continue for one and a half or more years before spontaneous remission. Standard treatment requires at least two to four weeks to begin to cause a response. It is good that the FDA has approved two new medications (Zulresso and Zurzuvae) for treating postpartum depression.

Brexanolone (brand name Zulresso) is a drug approved by the FDA in

2019 with unique actions. It requires gradual intravenous infusion over a period of 60

hours and must be administered in the hospital. This is the first FDA-approved

drug for postpartum depression. It is presumed to have actions on

allopregnanolone, a neuro-steroid that has actions on the GABA system (Brody, 2018). With premenstrual depression and postpartum depressions, allopregnanolone

levels drop precipitously. Progesterone may be targeted by the drug but the precise

mechanism of action is unknown at the time of this course update. Typically,

30% of women experience a significant and rapid reduction in psychiatric

symptoms. The drug may have enduring positive effects for at least a month, but

longer-term follow-up studies have not been done to date. The cost of the

medication alone is currently $34,000, which does not include the cost of the

hospital stay and the clinicians involved. The most common side effects are

sedation, dizziness, dry mouth, loss of consciousness, and flushing.

Zuranolone (brand name Zurzuvae) is the first oral pill to treat postpartum

depression. It has been approved by the FDA since August, 2023. It can be given

with fat-containing food for 14 days. It works fast, in three days, and

remission is about 60% at six weeks. It improves anxiety symptoms as well. It has

a similar action as brexanolone. The common side effects are sedation,

dizziness, dry mouth, loss of consciousness, and flushing. However, the

medication trials haven’t included breastfeeding women.

Research is ongoing with other possibilities such as using a sedative, dexmedetomidine, another medication administered intravenously for 48 hours in the hospital. This medication was given immediately after giving birth, to women who had prenatal depression. It appeared to significantly reduce postpartum depression. The study was done in China and the sample was small (Zhou, 2024).

New Treatments and Interventional Treatment for Major Depressive Disorder

While the most common treatment for major depression is to use a traditional treatment, that is, an antidepressant, a better understanding of the pathophysiology underlying many mental illnesses has led to the recent increased use of treatments that require specialized administration and the creation of a subspecialty called interventional psychiatry. For example, we have mentioned Brexanolone (brand name Zulresso), an intravenousdrug for postpartum depression. We have esketamine, a nasal spray for refractory depression treatment as well. Other interventional treatments for depression are rTMS, vagus nerve stimulation, and ECT.

Esketamine (Brand name: Spravato) The drug ketamine has been used in

medicine and veterinary medicine for years as an anesthetic. It also has been

abused as a street drug because of its dissociative and hallucinogenic

properties (on the street it is often referred to as Special K). It

is also widely used in psychiatry mainly in ketamine clinics to treat severe,

treatment-refractory depression and especially acute, severe suicide risk. In

psychiatry, it is used off label and administered typically twice a week in the

clinic, because it requires IV dosing and a period of two to three hours of

patient observation afterward. This is because dissociative and some psychotic

symptoms exist for a period of several hours after dosing. Some severely affected

patients respond rapidly to the antidepressant effects. Also, there is often a

rapid decrease in suicidal ideation and impulses. It has also been used

successfully to treat patients with psychotic depressive episodes.

Recently, the active S isomer of Ketamine (esketamine; brand name Spravato) has been approved by the FDA (March, 2019), to treat refractory depression and/or acute suicidal risk. It is available in a nasal spray.

Because of its abuse potential, it is tightly regulated by both pharmacies and

treatment facilities. It must be administered in a treatment facility that has been

certificated in Spravato Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS). The

duration of effects and even the frequency of dosing is largely unknown.

S-Ketamine is a glutamate NMDA antagonist, although its specific mechanism of

action is largely unknown. In many individuals, however, the effects are seen

within minutes to hours. The success of S-Ketamine opens the door for future

drug development because its action on glutamate is clearly different than

other, standard antidepressants.

Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) In TMS, a series of magnetic pulses are administered via the scalp to stimulate neurons in areas of the brain associated with major depressive disorder (MDD). It is considered a non-invasive treatment for MDD. The initial recommended course of treatment is six weeks, but most improvement is seen in the first two to three weeks. After six weeks of treatment, many patients require ongoing maintenance treatment, which can be weekly or monthly based on response. The repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is the first one approved by the FDA, in 2008. As TMS technique has improved, we can do deep TMS, intermittent Theta burst stimulants, navigated TMS, and accelerated TMS to improve symptoms quickly. Some recent studies indicate there is potential to identify which patiens are most likely to respond to TMS.(Cosmo, et al., 2021).

Vagus Nerve Stimulation is a technique that was initially developed to treat severe epilepsy. It has been found to be effective in successfully treating about 50% to 60% of people who suffer from highly treatment-resistant depressions. The FDA approved it to treat chronic Treatment Resistant Depression (TRD) in 2005. A pacemaker-like device is implanted in the anterior chest wall (beneath the collar bone) and a wire extends up into the neck where it is wrapped around the left vagus nerve. Periodically, a mild electrical stimulation is delivered to the vagus nerve, which causes nerve activity that enters the brain. Due to the cost of the procedure and risks related to surgery, it has not been used widely in psychiatry.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) Although ECT is used to treat psychiatric

illnesses ranging from mood disorders to psychotic disorders and catatonia, it

is mainly employed to treat people with severe treatment-resistant depression

(TRD). It is one of the most effective treatments for major depressive disorder,

and can significantly improve patients’ quality of life. During ECT treatment, the

patient can continue to be on antidepressants.

Herbs and Supplements for Major Depressive Disorder

A number of experimental treatments are widely used by people who

have experienced depression, especially people who try over-the-counter

supplements and herbs. To help symptoms of depression, people have tried omega-3

fatty acid supplementation (Peet and Horrobin, 2002), SAM-e, and St. John’s

Wort. It is recommended that if your patient is considering using them, the efficacy

and safety may not be established. It should only be taken with close

observation by their treating mental health professional.

Omega-3 Fatty Acids are dietary supplements that have some research support as

effective agents in reducing the severity of bipolar mood swings and major

depression (when added to standard medication treatments (Stoll, et al., 1999).

The responses in bipolar patients, however, have been disappointingly minimal,

while a number of studies do show positive responses when used in unipolar

depression. Doses that are used to treat or augment treatment of depression are

1000 to 2000 mg per day (EPA: the specific type of omega 3 that has an

impact on mood). Fish oil sources of omega 3 have greater bioavailability in

the brain and are more effective than omega 3 from flax seed or walnut oil. If

you want to know more about omega 3, please see NIH omega-3 fatty acids: health

professional fact sheet.

SAM-e (S-adenosylmethionine) is a naturally occurring bio-molecule found in most living

cells. It is felt to be necessary for carrying out a number of important

intracellular chemical reactions. SAM-e has been used in Europe for more than

20 years as a treatment for depression. Some studies have shown it to be

equally effective when compared to prescription antidepressants, while others do

not show any benefits or only minimal effectiveness. Most notable is the

virtual lack of side effects. Doses for the treatment of depression range from

400-1600 mg per day, although recent investigations indicate that often the

higher doses (1200-1600 mg per day) may be necessary for effectively reducing

depressive symptoms. SAM-e may be useful in treating bipolar depression,

however, one must exercise caution because it has, in fact, been found to

switch people with bipolar depression into states of mania.

St. John’s Wort is an over-the-counter dietary supplement that has been found to

have antidepressant properties. A meta-analysis of 22 studies has shown that

St. John’s Wort is equally effective to prescription antidepressants in the

treatment of mild-to-moderate depression (Lined, et al., 2008). This herbal

remedy is generally well tolerated with few if any side effects. There are

reported cases of possible infertility problems associated with its use,

although it is as yet unclear whether this is a common side effect. St. John’s

Wort requires daily dosing of 900-1800 mg. (taken in three divided doses), and

typically the first signs of symptom improvement take about six weeks to

emerge. Thus, the onset of action is somewhat longer than that seen with

prescription antidepressants. And as with any other treatment that has

antidepressant properties, St. John’s Wort can potentially provoke mania in

people with bipolar illness. Caution: although St. John’s Wort, when it is the

only medication being taken, appears to be quite safe, it has been found to

cause some very significant drug-drug interactions. It is strongly advised that

patients never take St. John’s Wort without first consulting with their

physician or pharmacist.

Oxytocin is

a hormone normally produced in the hypothalamus and released by the posterior

pituitary. Oxytocin may

influence depressive disorders by modifying stressor reactions. Oxytocin interacts

with the HPA axis, monoamines, and inflammatory factors. Social sensitivity

might be modulated by oxytocin thereby affecting negative affect (Mcquaid,

2014).

Combined Psychotherapy and Pharmacotherapy

Aside from its role as a primary treatment for some types of

depression, a number of studies have demonstrated that psychotherapy can

enhance treatment outcomes when combined with drug treatment (McCollough,

2000) and may contribute significantly to aiding in relapse prevention

(Reynolds, Frank, Perel, et al., 1999; Evans, Hollan, DeRubelis, et al., 1992;

Thase, Greenhouse, Frank, et al., 1997). Several authors including MacFarlane

(2003) and Whisman & Uebelacker (1999) advocate treatment models that

combine couple therapy with individual and pharmacological interventions for a

more integrated treatment approach. Additionally, the psychotherapist is in the

best position for closely monitoring adherence, side-effect problems, and

clinical response to medication treatment. This is especially important if the

client is being treated in a primary care setting where the therapist can

collaborate with the physician in order to optimize treatment outcomes.

Antidepressants

and Increased Risk for Suicide |

There has been a good deal of media

attention regarding potential risks of antidepressants and increased

suicidality (especially in children and adolescents). The initial concern

came from studies in England that raised concerns about increased suicidality

in young patients treated with the antidepressant Paxil. In this study, which

included 1,300 patients, Paxil was compared to placebo and reports of

increased suicidality were seen in 1.2% of placebo and 3.4% of Paxil-treated

subjects. This difference is statistically significant. It is important to

note that there were no actual suicides in this group of youngsters. A

problem is that “suicidality” has been very loosely defined in this and other

studies. Most times it includes reports of increased thoughts about suicide,

suicide gestures, non-lethal-intent, tension-reducing self-harm (as is often

seen in borderline personality disorders), and in one instance a report of a

child slapping herself. (Brown University, 2004). Of course, actual suicides

and lethal attempts are also included under this umbrella of suicidality. The

FDA has responded to concerns about increased suicidality by requiring drug

companies to issue warnings about the use of these drugs with younger

clients. Since the media blitz regarding antidepressants and suicidality in

youngsters, prescriptions written for children and teenagers have decreased

by 30%-40%. There has been a corresponding increase in reported suicidal

ideations among depressed youngsters, but not an increase in

actual suicides. The FDA has reviewed a number of studies focusing on the use

of antidepressants in youth. The total number of subjects in these studies is

4,400. The risk of treatment-emergent suicidal events is approximately 2% in

those treated with either no medications or placebo and 4% of those treated

with antidepressants. The most common “suicidal event” is suicidal ideations.

In the group of 4,400 subjects, there were no actual suicides.

What is clear is that untreated major

depression carries extreme risks of potential suicide, antidepressants take

several weeks of treatment before the first signs of clinical improvement, and

depression can worsen during this startup period of treatment. This can

happen in both drug treatment as well as psychotherapy, and thus therapists

must be watchful for treatment-emergent suicidality regardless of treatment

used. Antidepressants can cause an acute increase in anxiety and agitation

during the first ten days of treatment (i.e., activation: affecting about 10%

of adults treated and 10%-15% of children and young adolescents treated)

which could contribute to increased dysphoria. Maybe more importantly, among

teenagers presenting with major depression, 40% turn out to have bipolar

disorder. This is true for 50% of pre-adolescent children with major

depression. Antidepressants are known to pose risks for precipitating mania

in bipolar patients. In younger people, mixed mania is very common in bipolar

disorder and dysphoric mania is accompanied by significant suicide risk,

Thus, in treating major depression it is very important to make sure the

depression is not associated with bipolar disorder before prescribing

antidepressants. Finally, it is always important to differentiate between

media hype and scientific data.

In

2004, the FDA required a black box warning related to increased

risk of suicidality in pediatric patients for all antidepressant drugs, and

in 2007 extended the warning to include patients up to age 24. |

|

Bipolar Spectrum Disorders

Introduction and Diagnostic Issues

Bipolar disorder is a common type of mood disorder that is a

recurrent and often chronic mental illness marked by episodes of hypomania or

mania and depression, associated with a change or impairment in function. It

includes bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, cyclothymic disorder, substance/medication

induced bipolar and related disorder, bipolar and related disorder due to

another medical condition and other specified bipolar disorder, and unspecified

bipolar disorder. The lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder type I in the US

is estimated to be between 0.5% and 1.0%, affecting men and women equally. The

lifetime prevalence of bipolar II disorder in the US is estimated to be between

0.5% and 1.1%, with women more likely than men to be affected.

This is an introductory course on bipolar spectrum disorder. If you want to learn more, please see the course on this website called Bipolar Spectrum Disorders: Diagnosis and Pharmacologic

Treatment.

Symptoms of Classic Mania

- Euphoria or an

inflated sense of self-worth

- Restlessness,

agitation, hyperactivity

- Decreased need for

sleep (e.g., sleeping 3-4 hours per night, yet without daytime fatigue)

- Racing thoughts and

rapid, pressured speech

- Poor judgment and

impulsive behavior, e.g., spending atypically large amounts of money, driving

fast/recklessly, marked alcohol or drug abuse, promiscuity and engaging in

unsafe sex

- Psychotic symptoms can

occur

Symptoms of Hypomania

Hypomania is a milder version of mania that typically involves

much less intense mood symptoms. The duration of hypomania is at least four

days and is frequently not noticed as being a sign of illness by the person

experiencing it (although most times family members are more clearly aware of

the mood changes and increased energy). During the hypomanic episode, the

person can feel highly motivated and productive, is witty, gregarious and

“upbeat”, although there is often underlying irritability. One very common

sign of hypomania is a decreased need for sleep with no daytime fatigue.

Symptoms of Mania or Hypomania with Mixed Features

- Dysphoria or negative or pessimistic

mood

- Diminished interest or

pleasure

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness

or excessive guilt

There are five main subtypes of bipolar disorder and one controversial subtype:

- Bipolar I: severe manic (classic or dysphoric) and

depressive episodes (often with periods of normal/euthymic mood between

episodes).

- Bipolar

II (including hypomania and depression): characterized by frequent, severe and prolonged

depressions with periodic, brief episodes of hypomania. A normal/euthymic mood

can occur between episodes, but often during these in-between times there is a

low-grade/mildly depressed and/or irritable mood. Judd, et al. (2002) studied

the course of bipolar II disorder for a period of ten years and found that 15%

of days were spent in major depressions, 40% in minor depressions and only 1.4%

in hypomania.

- Cyclothymia: a chronic, fluctuating mood disturbance in

which symptoms of mood changes do not meet the full criteria for depression and

hypomania. (Note: this less severe version of bipolar can become worse with time

and up to one-half of people with cyclothymia eventually convert to Bipolar I

or Bipolar II.

- Substance/Medication-Induced Bipolar and Related Disorders: By the history taken from the patient, their physical examination, or laboratory findings, the symptoms of mania or hypomania are found to have developed during or soon after substance intoxication or withdrawal, or after exposure to or withdrawal from a medication. We know substance use and medication can induce mood changes.

- Bipolar and Related Disorder Due to Another Medical Condition: It is clear from the history taken from the patient and the physical examination, that the mood changes (mania, hypomania, and depression) are directly caused by the medical condition.

- Pediatric or Pre-pubertal Bipolar Disorder: In the 1990’s researchers in the U.S. proposed that certain behaviors in children, such as chronic irritability and explosive temper along with such diagnoses as ADHD, might actually be a form of mania. International research, however, did not seem to bear this out with a significantly lower prevalence and thus, the existence of this category is still being debated. In addition, there is much disagreement over assessment tools, such as using checklists for diagnosis. The newest DSM-5 category of DMDD may be an alternate diagnosis for many of these children. For a fuller discussion see (Duffy, et al. 2020)

If the patient’s symptoms do not fully meet the criteria for

mania, hypomania, or depression, however, and their symptoms still cause

clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other

important areas of functioning, we call them “Other Specified Bipolar and

Related Disorder and Unspecified Bipolar and Related Disorder”.

“Rapid cycling”is one of the specifiers we commonly hear about. It requires at least four mood episodes within the previous 12 months and these mood episodes have met the criteria for a manic, hypomanic, or major depressive episode. These episodes can occur in any combination and order. Lifetime prevalence ranges from 26%-45% of those with bipolar disorder. Although the exact etiology is unknown, use of substances or antidepressants seem to be related. For most, rapid cycling is a temporary condition. While rapid cycling can lead to a worse outcome, early recognition and treatment can improve the outcome (Carvalho, A.F.et al., 2013).

Treatments for Bipolar Disorder

Untreated or poorly treated bipolar illness leads to disaster. Careers and marriages can be ruined, physical health problems abound, and there is a high rate of suicide (19%-20% lifetime risk). If not treated, most cases of bipolar disorder become progressively worse, likely owing to kindling effects. The sooner this illness can be diagnosed and properly treated, the better.

Although the focus of this course is on psychopharmacology, we

will also briefly address adjunctive treatments. Medication treatment alone is

never adequate to fully control bipolar disorders. Treatment must have a

two-pronged focus: bringing to an end the current manic or depressive episode,

and relapse prevention. With proper medical treatment, most people can

experience a marked decrease in episode frequency and severity.

Lifestyle Management

People with bipolar illness have very unstable and fragile neurobiological

mechanisms for affect-regulation. Extreme emotional lability and mood

episodes can be triggered by a number of environmental, psychological, and

physiological stressors. Before a discussion of medication treatment, we will

address lifestyle management issues. It is especially important to regulate

one's lifestyle closely, because without this, medical treatments often are only

partially effective (Malkoff-Schwartz, et al., 1998). Most important are:

- Maintain regular bedtimes

and awakening times. Such regularities in sleep patterns are crucial;

- Avoid substance abuse

and alcohol use/abuse like the plague (substance abuse is very common in

bipolar disorder and often significantly aggravates the illness);

- Avoid sleep

deprivation, shift work, and crossing time zones;

- Avoid or greatly

minimize caffeine use since it can significantly disrupt the quality of sleep;

and

- Keep the amount of

bright light exposure (e.g., sunlight) and the amount of physical exercise

consistent each day year-round.

Medication Treatments

General Considerations

General references:

- Hirschfeld, et al.

(2002): Bipolar disorder Practice Guidelines

- Goodwin and Jamison

Manic Depressive Illness (2007)

- Texas Department of

Mental Health (1998) Texas Medication Algorithm Project

- National Institute of

Mental Health (2006) STEP-BD Program

- American Psychiatric

Association: (2002) Bipolar Disorder Practice Guidelines: Second Edition.

Currently, there are many medications that are approved by the FDA

for the treatment of bipolar disorder: Lithium, Depakote, Equetro, Lamictal,

Symbyax, Zyprexa, Risperdal, Seroquel, Geodon, Abilify, Latuda, Saphris,

Vraylar, and Caplyta. However, a number of other effective drugs are in common

use. The use of medications not approved by the FDA for the treatment of

certain conditions is referred to as “off-label use.” It is important to note